In 1971, Gilbert and George were asked why they had picked Gordon’s for their piece ‘Gordon’s makes us very drunk’ and their answer was: “Because it is the best gin.” For the film, they added their names to the bottle’s label on either side of the Royal crest. Soundtrack was by Elgar and Grieg. At the time there was no alternative to the Schweppes tonic.

In 1971, Gilbert and George were asked why they had picked Gordon’s for their piece ‘Gordon’s makes us very drunk’ and their answer was: “Because it is the best gin.” For the film, they added their names to the bottle’s label on either side of the Royal crest. Soundtrack was by Elgar and Grieg. At the time there was no alternative to the Schweppes tonic.  Nowadays all bars tend to ignore Gordon’s. You have to go to the airport or to the train station to drink it. Only Gordon’s with Schweppes gives me that light feeling of celebration and revolution in the afternoon. And the smell of African juniper the next morning. All people who ordered G&T the first night I met them, became friends. Do you really want to talk about beer or––even worse––talk about wine? Good Lord.

Nowadays all bars tend to ignore Gordon’s. You have to go to the airport or to the train station to drink it. Only Gordon’s with Schweppes gives me that light feeling of celebration and revolution in the afternoon. And the smell of African juniper the next morning. All people who ordered G&T the first night I met them, became friends. Do you really want to talk about beer or––even worse––talk about wine? Good Lord.

Gin and Electronics

After Eva’s Sunday manifesto, it is admittedly hard to decide what, and how to write. How to continue, and what to decide. Let’s go where it hurts, she wrote. Austerity instead of oysters. She even used exclamation marks! Manifestos always make me sad. There is a distinct melancholy to them, a clandestine consumption, a nostalgia for something that has not yet happened. The true impact of the manifesto is the virtual, oscillating, scintillating moment, present and absent. Even though writing inscribes and stores, can it transmit the unnamable? »In at one ear and incontinent out through the mouth, or the other ear, that’s possible too. No sense in multiplying the occasions of error. Two holes and me in the middle, slightly choked. Or a single one, entrance and exit, where the words swarm and jostle like ants, hasty, indifferent, bringing nothing, taking nothing away, too light to leave a mark.« [Beckett, The Unnamable] »Wer, wenn nicht diejenigen unter Ihnen, die ein schweres Los getroffen hat, könnte besser bezeugen, dass unsere Kraft weiter reicht als unser Unglück, dass man, um vieles beraubt, sich zu erheben weiss, dass man enttäuscht, und das heisst, ohne Täuschung, zu leben vermag. Ich glaube, dass dem Menschen eine Art des Stolzes erlaubt ist – der Stolz dessen, der in der Dunkelheit der Welt nicht aufgibt und nicht aufhört, nach dem Rechten zu sehen.« [Bachmann, Die Wahrheit ist dem Menschen zumutbar] I wasn’t there when Eva, Georg, Sam, and Carson plotted the coming insurrection. I will comply and write about juniper-based highballs: I do not particularly like Gin and Tonic, although it has been ever present in my life for the past ten years, being Friedrich Kittler’s signature drink. Every Tuesday and Thursday, after the first early afternoon classes in the brickstone factory building in Sophienstraße the Chair für Aesthetics and History of Media was located in, we’d head over to Oxymoron, Kittler’s main haunt, where he inexplicably also got a 20% discount. The usual fair during the two hours before evening class – his legendarily smokey “Oberseminar” or the programming course we taught together – comprised of a meticulously mixed Gin and Tonic, and maybe another one, or a bouillabaisse, if he was hungry. You can actually go there and try to order a “Kittler”. If the waiter has been there long enough, he’ll know. It’s not a regular Gin and Tonic. It comes in modular form. 4 cl of Tanqueray Gin, a small bottle of Schweppes Tonic Water, a quartered lime, and a glass of ice cubes, to be mixed yourself to avoid a watering down because of the ice. At his Treptow apartment, the usual was: “Sie wissen ja, wo alles steht, Herr Feigelfeld.” We would then debug C code.

We sat in an Izakaya in Tokyo on a Friday night and every time Fabian wanted to order a single thing (beer, shōchū, yakitori) he got two of the same. He said hitotsu (Japanese for one thing), and got futatsu (2) all the time. It was mysterious. And then we sat in one of those micro bars, usually around the stations, where 4 to 5 people can squeeze in and we drank, I don’t know, maybe Chilean white wine. And then we met in front of Kunsthalle Basel where he works. But that was before the micro bar, was it? And in-between we were riding home in a friend’s car and we had to stop, not because of Fabian, because somebody who always has to got to the toilet wanted to take pictures of the floor tiles in a public toilet between Zurich and Basel. It makes absolutely sense to take pictures of toilet walls. A girl once told me in Berlin in the Soho House I should take a picture of the wallpaper in the men’s toilets. What looks like harmless leaves are actually hidden vaginas painted into the leaves (maybe everybody in Berlin knows this, but not everybody is in Berlin). Fabian always wears those impeccable suits and he always takes pictures of the artists who are exhibiting in the Kunsthalle Basel (there are usually no hidden vaginas in the pictures). They have to stand in front of the Tinguely Fountain and they try to smile for whatever reason because I am sure Fabian would not ask them to smile. He takes an attitude of confronting you with whatever he thinks is confronting you.

I think Gin Tonic is austerity and hedonism at the same time. Getting drunk without getting pissed. You can have the cake and eat it all. It is a drink in an age of crisis. It is stabilty, security, without Spießigkeit. You can rely on Gin Tonic. You cannot do much wrong with Gin Tonic. But you also can have a lot of fun with Gin Tonic. You don’t have to think about the consequences, really. You will be fine. That is the message. That is the feeling from the first sip on, actually maybe already from the moment that you order the drink. It arrives, a lot of ice, an indefinite amount of Gin. Some vegetable or not. And the Tonic. Some people will never talk to you again if you drink Schweppes. I am not one of them. But I understand that there are better Tonics. Anyway: You pour the Tonic. You taste the Gin. The drink is always too strong at the beginning and not strong enough at the end, which is odd. Imbalanced balance. Imperfection throughout. And yet total conviction. It is a convincing drink. And it starts always well. The drunkenness builds slowly. First the drink is only refreshing. Then you start to feel it. You talk more, you think faster, you are more daring. But you are still in command. It is a drink about authority. It is a drink for non-drinkers as well as for professional drinkers. Experts love it, as do people who either don’t know anything about liquor or don’t want to know anything or just hate any kind of connoisseurship. Gin Tonic is anti-connoisseurship and in that sense the rebuttal of anything the Nineties were about. Or the 2000s, people much too young sitting in bars and talking about Whiskey. Are you serious? You can bore people for hours talking about Highland and Lowland or Single or Double or whatever. You can talk only for half a minute about Gin. Really. This is quite enough. I am not saying that there isn’t a certain degree of expertise in it which is always fine in a late night setting or early in an evening that might or might not end well. This is after the age of the expert. Everybody knows something. Which can be bothering. Especially if they are not the owner of the bar or the barkeeper. Even they can be a nuisance. So Gin Tonic is a drink without excuses. You cannot hide behind some bullshit. You have to be funny. Or smart. Or sad yourself. You have to be you. There is this clarity in Gin Tonic. It is a drink for talking, not for silence. It is a drink for conversation, even long conversations. You can go on and on drinking Gin Tonic. It is also a smooth drink, a seductive drink, both for men and women, both in the hand of men and women. It is a unisex drink in an unisex age which does not mean that it is not sexual. It is what it is, and also the contrary. A hybrid drink that could be anything you wanted it to be. Only recently you had to start making decisions, Hendrick’s, Tanqueray, Beefeater 24, Blackfriar’s, Bloom, of course our very own Monkey 47. This took some of the ease out of the Gin Tonic. But you can still avoid decisions which can be good in any situation, mood, environment. In the sleeziest place, in the most desperate moment, with the most thrilling or boring people, it can be a good choice not to have to decide. Men in general, I would say, like this drink because they can avoid doing the wrong thing and feel manly at the same time. They don’t have to think too hard. Women on the contrary have a drink that leads them out of the longdrinks ghetto of effeminate nonsense with little paper umbrellas. It gives them the power they already have. Still, you have to take what is yours, again and again. This is Gin Tonic. There is, I would say, a certain emancipatory spirit in it that is rare, in people as in alcohol.

Georg thinks about Gin & Tonic. I try to join with a mashed hangover brain. First of all, I resigned from Gin and Tonic a while ago after a short but disastrous period of overdosed gin consumption. The only exception was at our wonderful rainy kick-off walk over Alexanderplatz infused with Georg’s Alexanderplatz long read tasting – probably the most enjoyable scenic reading session I remember. Since ever, and particularly when approaching Alexanderplatz from Karl-Marx-Allee my wandering view sticks at this indescribably grey building, with probably hundreds of small square windows, which drives my phantasy towards darkness. A Gulag that has been forgotten to be removed. Then, with a grin that always lifts my spirit, I think of these lovely sayings: ‘Aus’m Alex wird nie was’ and ‘Spiel nicht mit den Schmuddelkindern’. These became something like a joyful imperative to me to look at many things, a key to how a society would keep its’ vitality and social mobility because life is in many ways about resilience and overcoming disrespect. It was really nice to meet the polite guys who put up the little bar to serve us Gin & Tonic after the scenic walk, and if we didn’t store ourselves in the tiny trailer box that sheltered us from the rain until the servants were ready, it would have felt a bit decadent to have us gentlewomen and men waiting to be served drinks. Vodka was New Berlin that lived up between the still standing ruins from second world war. Vodka leveraged the moneyless from a mentality of early post-war-era-austerity to a defiant yes we can. Vodka is potato. Vodka is Russia that conquered space but whose cosmonauts would still use five penny pencils instead of seven million dollar space pens which the NASA provided to their astronauts just to make notes in zero gravity. Vodka is occupy the new capital with nothing. Gin is The Empire. Tonic is the colonial emissary researcher, way too pale for the jungle, but too ambitious and curious to not find and examine the last undiscovered insect. Insects that provide the chitin which serves as the main ingredient of Tonic. Gin is the light handed gentleman standing in a club, but not the one we used to have in Berlin when dirty deeds were done dirt cheap. That’s done. I still prefer Vodka. It just brings me best through the night.

Tarun Kade

Alex and I share both our office and our birthday. This combination has led to one of my favourite birthday parties so far. The party gives a good impression of Alex’s character. First of all it is hard to imagine Alex not celebrating his birthday. When some of us like to withdraw ourselves from the world when we have to face the bitter fact of “another year gone by”, Alex likes to share these moments and make it an occasion for people to come together. And people really like to come together when Alex invites them to, he has the ability to create moments of absolute presence, which normally ends in euphoric bodily reactions. For our birthday party, he forced me to remove all the furniture from our office (very hard work). After that he installed colour changing LED-Lights, prepared big bowls of secret recipe punch and made me organize a slightly over dimensional audio system. Shortly before the party started he presented a performance on the roof of the building that included thousands of bees, an electronic drone (these military spying tools that have caused a lot of outcry recently and caused Alex’s eyes to glow––they do whenever he is unwrapping one of his regular packages filled with electronic toys) and himself. The actual party developed in such a way that the next day all alcoholic beverages in the theatre building had mysteriously disappeared and a whole day of cleaning had to be spent on theatre premises. But months later people still talk about it. Alex is not especially employed for parties at the theatre, he is artist-in-residence, something that had not existed before he arrived. There is no actual job description. But provide Alex with a room and some electronic equipment and he will create moments of pure presence. Art – right now!

I want to start a little project: I want to uncover the meaning of Gin and Tonic. What is it about this drink? Why is it so of this moment? Why is the moment so Gin and Tonic? Where was it a while ago? Why is it everywhere now? Why is there no alternative? Is there no alternative? What is the secret? What is the truth? What is the lie? What is the myth? What are the facts? What is the story? Tell me, 60pages. I want to know. From you. So help me. Let’s write this story together. It is a story about today. It is a story about us.

Every Tuesday afternoon at 3:30 I go to high school. The school is in Wedding, in a grand old pre-war building, with echoing halls, fluorescent overhead lights, and Koreans who can’t find their classrooms. I ignore their beseeching looks – I’m late to class myself – and take the stairs two at a time.

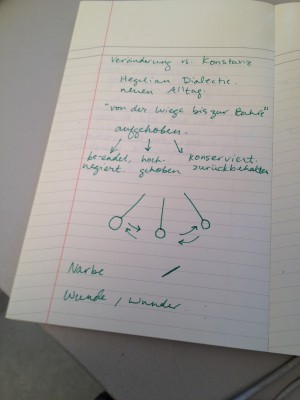

Inside Room 304, Reinhard, my philosophy teacher, is holding forth. I get out paper and pen and take furious notes:

Of course, I’m not really in high school. I’m just at the local Volkshochschule, an adult education center, which offers a philosophy class for non-native speakers. But everything about the setup screams being sixteen – sitting behind a desk; Reinhard’s easy charisma and wild gray hair, like the most popular high school teachers; the strong smell of floor wax; and my dorked-out joy, as I jot down the three different meanings of aufgehoben, and come up with a nifty pendulum illustration (which I’m pretty sure I also drew in 1998, when I was in high school in Singapore, learning about Hegel from my then-history teacher, Mr. Dodge). The fact that aufgehoben somehow simultaneously means nullified, lifted up, and held back makes more sense than anything has all week.

The Portuguese student raises his hand and volunteers a lengthy response to Hegel’s Dialectic, something involving Wunder that no one, not even Reinhard, understands. The Portuguese guy repeats it three times, to utterly blank looks, and then says forget it. This is a common occurrence. All of us can understand what Reinhard is saying, but we can’t understand each other, and find it hard to articulate, in German, what we think about being and nothingness.

Start over, Reinhard prompts the student. What does Hegel have to do with Wunder?

I think he’s talking about Wunde, nicht Wunder, says the other American woman in class.

Ja, the Portuguese guy says, relieved. Wunde, nicht Wunder. Wunde und Narben.

Wounds, not miracles. Wounds and Scars.

I jot this down, too. It seems like a crucial insight.

Later in the class, Reinhard hands out the poem “Stufen” by Hermann Hesse, and asks if we know the song “Turn, Turn, Turn” by Pete Seeger. There is a nervous silence, in which the American woman and I exchange looks, and somehow, I’m suddenly singing the song like I really mean it: “And a time to every purpose, under heaven.” I get a look from Reinhard like that’s enough before I hit the chorus, so I clear my throat and stop, disappointed that nobody claps.

That’s maybe the best thing about going to high school when you’re 32, you can sing a Byrds song without worrying if your bra strap is showing or if your shorts look weird or what the other kids think of the fact that you know the song by heart. And you can take notes that say “IMPERATIV! Stirb und Werde.” (Imperative! Die and Become.)

It was a place where you speak English when you order and are surprised if the guy behind the counter who might or might not have been gay – it is hard to tell these days with the fashion in beards – answers in German. I had never been to this part of Friedrichshain and neither had Christopher, actually it was the part of town you only go to when you meet somebody who speaks English, I would say. A very nice part of Friedrichshain, Oderstraße, there is a large playground there, trees, it is calm, and there is Aunt Benny, a pleasant café where you get a small thing with a number written on it when you order and wait outside in the cold until the sun reaches across the houses and an Asian looking girl brings you your Chai Tea Latte. It all seems like a very small part of Brooklyn or Notting Hill brought to Berlin. Or is Berlin just a very small part of Brooklyn or London anyway? Victoria had suggested the place, she lives near Warschauer Straße, she said, in a different area, she said – I would have said that it is the same neighbourhood. Which just goes to show how little I know: of Berlin, of my time, of a few things. This is why we met Victoria. To help us. To move us along. To work with us. She is from Birmingham which is fine because neither of us has been there. She runs a blog about Neukölln which is fine because neither of us do. She was recommended to us by a woman with the nice name Ché Zara Blomfield who again was approached by Elvia Wilk who was brought to our notice by Gideon Lewis-Kraus, all three very nice names. As is Victoria. Gisborne-Land. We should ask her about this name, shouldn’t we?

The first time I met him, I think, was at the store or gallery that he used to have on Potsdamer Straße before it became Potsdamer Straße. He was standing in the middle of all the furniture that he was designing at the time, lamps and tables made out of wood that was painted grey or white or black, very cubist in a way, very simple, very beautiful and very different from the stuff that he had stored in the back, his old life, so to speak – vintage Aalto chairs, Italian stuff, some Perriand stools, beautiful too, but he was done with that. It does not make sense to pay 3000 Euros for a stool, he said. It might even be amoral. He is Swiss, you know, I think. Are you Swiss, Clemens? Why do I think that you are? Because you are very rational? Because you speak in a very soft voice? Because you care? Well, you left Potsdamer Straße, obviously, as it became Potsdamer Straße, I don*t even know where your store is at the moment or if you have a store – we only met again a while ago in Paris at Hedi Slimane*s first show for Saint Laurent. I liked the show, you liked it too, I think, even though you were very sceptical, but that*s because you like Hedi so much. The show was about the woman as a western figure, it was a new woman that looked like she was from the 70s, she was proud and sexy in a very careless, maybe even dangerous way with great great leather pants in beige suede and large hats and shirts with frizzles, if that is the word, you know what I mean. Were you disappointed, Clemens? Hedi Slimane was so big in the years 2000. He defined what it could mean to be a man. Could he define what it means to be a women in the years 2010? I think the verdict is still out on that. You looked for Hedi after the show, but he was already on his way back to Los Angeles. We had dinner instead, the two of us, in this nice restaurant au bord de la Seine or somewhere, close to the Mairie. We both have not been back at one of Hedi*s shows.