Lately I’ve been watching Huffington Post Live in the evenings while I’m cooking stir fry or folding my laundry. Like watching The Bachelorette or going to art fairs, I think of watching HPL as an anthropological activity, in this case one that belies an awkward homesickness for the vulgarities of American culture. HPL is the media company’s live-streaming web-tv site, an endless string of four- to ten-minute chunks of “the biggest, hottest, and most engaging stories of the moment” – a three-ring circus of inane debates between whoever is on hand and can get sufficiently outraged/”huffed up” at that moment (remember, it’s endless, and it’s LIVE), feel-good stories about dogs and/or Google’s latest charity venture, and interviews with entrepreneurs and tech gurus about apps, apps, apppppppssssss.

(Last week while frying Chinese cabbage I watched a phone-in interview with a lady protester in Ukraine who manages to be hot while political, a Buddhist monk meditating LIVE, a re-stream of a Ted Talk with a (female but old) geneticist who Google just hired for its AIDS-stopping task force, and a black guy tirading against racism in American culture – who, amazingly, was interrupted in the middle of his rant by call-ins from two black women accusing him of sexism. Trump card!)

One of the most feeling-good stories I’ve seen recently was an interview with Sarah Lewis, author of The Gift of Failure. During the interview the breathless segment host(ess) brought in another guest via Google Hangout: Diane Loviglio, the San Francisco producer of FailCon, which is “a conference for startup founders to study their own and others’ failures and prepare for success.” At FailCons around the world, famous and/or rich (=successful) people meet up and tell stories about the miserable failures they have endured throughout their lives, which, remarkably, and through sheer will, THEY OVERCAME. These survivors testify the the importance of the “taboo topic” of failure before a rapt audience of soon-to-be-successes, with what I imagine to be uplifting slide shows and not a tinge of self-righteousness, each speaker driven simply by the charitable impulse to inspire others.

If you are looking for evidence of late-stage capitalism’s ability to extract value from every single waking moment (and possibly sleeping moments too), FailCon is pure gold. Can you imagine a more brilliant maneuver for wringing value out of every moment of personal non-productivity than wringing money out of those who haven’t produced enough value yet? FYI, the woman who started FailCon managed to capitalize upon her entire failed life by starting FailCon.

FailCon is the next level self-help book. And by capitalizing upon what it deems to be failure, it clearly demonstrates how failure – by which we mean unproductivity, inability to produce value within the system – is, contrary to the conference’s explicit message, completely unacceptable and incompatible with the logic of the global economy.

Jonathan Crary writes: “when people have nothing further that can be taken from them, whether resources or labor power, they are quite simply disposable.” To be economically non-valuable is to be completely disenfranchised. But, if you are committed to actively contributing to the economy, failure is ok, as long as you can recycle it into a story to inspire others one day. Just like your start-up company recycles old coffee cups and cell phone batteries to produce the surplus value of environmental responsibility as a key priority on your company homepage.

Thought experiment: invite a bunch of migrant workers, disenfranchised immigrants, sex-slaves, and homeless people to a FailCon to inspire them with the message that if they work hard enough and exercise positive thinking every day they will one day achieve the startup dream, just like speaker Geoff Wilson, founder and president of the digital agency 352, which he started unsuccessfully 15 years ago out of a dorm room but was able to get past some “bumps in the road” to eventually, um, almost recoup the million dollars it initially blew. (You guys all have dorm rooms, right?) The lucky audience could even… one day… perhaps… be completely assured they have finally achieved success by being invited to speak at a FailCon! Or better, start a FailCon franchise themselves!

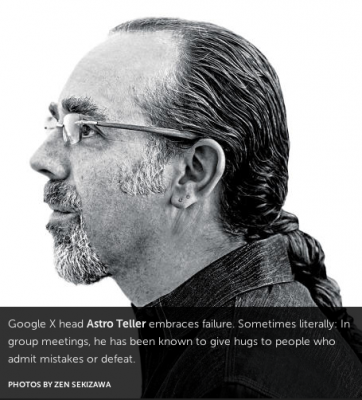

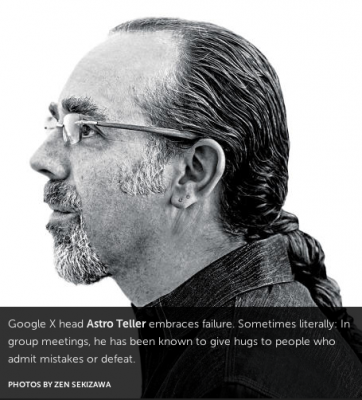

In John Gertner’s recent article about Google X on FastCompany, the awestruck, pandering tone of which makes me feel very uncomfortable, we get a glimpse of the secret behind the world’s most cutting-edge and well-funded think tank. The big secret: FAILURE. One leading team member says: “Why put off failing until tomorrow or next week if you can fail now?” Another tells the writer that he sometimes gives a hug to people who admit mistakes or defeat in group meetings. Gertner goes so far as to call the organization “a cult of failure.”

The cult at Google X, like the fetishizers over at FailCon, have created the opposite of what they propose: a situation in which you literally cannot fail. First, because the lady doth protest way too much, and putting such an obsessive emphasis on the word implies profound terror of real defeat, whatever you think defeat would look like. (Re: terror, can you imagine getting a billion dollars and being told by Google to invent something to change world?) Second, because if failure equals success, failure is not failure. It’s, uh, success.

And if failure can be instantly converted into success, there is proof that the system must be working. Burnout, misery, depression, grief; these may be personal failures that you are responsible for, but they are minor setbacks that you can overcome with determination. The system forces you to fail, and then feel redeemed and grateful when you succeed. Thank you benevolent system for allowing me to afford an iPhone after I had a Motorola for so long; now I can wake up in the middle of the night to check my three email accounts. #FAIL.

(Why exactly are the lucky few chosen to work at Google X considered successes and not miserable instruments/storefronts for a self-perpetuating corporation who is causing the very world problems it purports to solve by inventing hovercrafts? I might propose a majorly-funded think-tank or convention to re-evaluate our basic measures of success and failure. OH WAIT, Arianna Huffington has already begun a movement speaking out against productivity. Working 24/7 can no longer be the #HuffPostWoman’s mark of success!)

Resilience is the implicit word underlying the cult of failure. You will fail, and then you will bounce back to become a contributing member of society again, driven by your hardships to succeed even harder. Whether or not you read self-help books, and whether or not you are an entrepreneur or an artist or a talkshow host on HuffPost Live, you have been told since birth that failure is the key to success, and you know that cultivating the illusion (self-delusion) of breakdown is absolutely integral to the cycle of productivity that we are all locked into.

In an essay called Resisting Resilience, Mark Neocleous likens the rhetoric of resilience surrounding self-help-healed burnout with the language of militaries and governments – resilience after terrorist attacks, resilience from economic depression. It’s very worth reading. It convinced me that I should absolutely not attempt to better myself. I should stay a slob. Resist resilience. PRO BURNOUT. elviapw.com / 3LVVIA