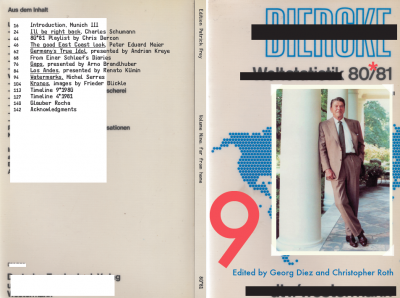

(In cooperation and with the generous support of Goethe Institute New Delhi / Max Mueller Bhavan)

Dear Aman,

I’d be happy to describe to you what’s going on in Germany at the moment – at least I’d be happy to try, because actually I don’t understand it myself. And incidentally that’s the way it is for most Germans – except for the ones who set refugee homes on fire: at least they know that they hate, and hate is what they’re looking for because they often have little to hold onto in their lives.

Everyone else, on the other hand, finds it difficult to say what kind of country they live in. Sometimes it seems like a dark Germany that scares them because the citizens flock together to form an obtuse mass. Then again it seems like a bright Germany that gives them courage because the citizens unite in solidarity. And then it seems like a dark Germany again in which the politicians cut their values and their humanity down a notch while the citizens provide the necessary help for everyone who needs it.

And there are many – 40,000, 80,000, 1.5 million people, from Syria, from Iraq, from Afghanistan, Pakistan, Eritrea or the Balkan states. They come because they’re fleeing from war and persecution in their homelands or in search of a better life for themselves and their children. Those are the numbers for this year, for Germany alone, and as always politics are made with those numbers, images are used to manipulate opinions, the media come under suspicion of being biased, etc.

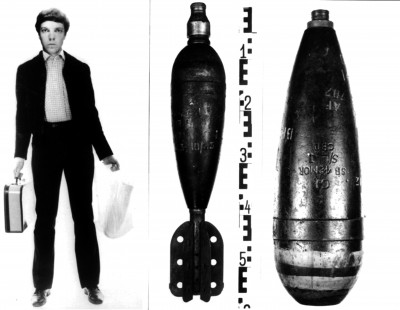

Could we have known that these people were coming? No, say the politicians who have been looking the other way for years, who have ignored the war in Syria, who were hoping the refugees would stay in the camps in Jordan or Lebanon, who thought the journeys would be too far and the ocean too wide and the fences too high – they didn’t know human nature very well, that’s evident once again; they’re not acquainted with the despair, they don’t know what volition all those people have who set out with only a plastic bag in their hand.

Yes, say those who’ve been dedicated to the refugees’ cause for years, who’ve been interested in the war in Syria, which has been like a gaping moral wound in the West for four years; yes, say those who think in historical dimensions and understand the large-scale geo-political devastation wrought by the Americans since they invaded Iraq and threw the country into turmoil because they weren’t willing or able to create a democratic order there the way they did in Germany after World War Two.

We could go back even further, to 1919 and Woodrow Wilson’s betrayal when, after World War One, he broke his promise of independence for many countries, or back even further to the nineteenth or even the eighteenth centuries to the havoc caused by colonialism, and perhaps we’ll get there in the course of our correspondence: as you can see, I really just want to tell you what’s happening here right now, in Berlin, where I live and where the refugees find themselves confronted with a bureaucracy that often comes across as sadistic in its Kafkaesque opacity – and no sooner do I start than the entire vast history of the world washes over me.

But perhaps that’s also quite apt for the current situation: because the fates of the individual human beings who come here mingle with fears that are older, raise questions that are more fundamental, open dimensions that are more permanent. When there is talk – rightly or wrongly – of a “new Völkerwanderung”, then already that choice of words alone suggests that we’re facing something between the Mongol invasions of Europe and the Turkish march on Vienna. And indeed, the fears that are often invoked are fears of “Überfremdung” (foreign infiltration) and in particular the “Islamisation” of the so-called “Abendland” (occident) – another word I haven’t heard for a very, very long time.

In a certain sense it’s as if Europe had woken up out of a slumber that lasted twenty-five years – and now that reality is breaking over this languishing continent in all its vehemence, many people seem overwhelmed. Until now, for example, Germany has had a hard time admitting that it’s an immigration country – at least conservative politics have refused to accept that reality. In the present situation that’s backlashing, because the country that essentially grants unqualified right of asylum – a circumstance rooted in the history of Nazi Germany – has no immigration law that corresponds to the current needs.

So much for today. There’s plenty I can still tell you: about our chancellor, who confuses everyone except herself, about scenes of the kind I’ve never seen in Europe, scenes of readiness to help and scenes of chaos, about my hopes and doubts, about optimism and pessimism. But I’d be more interested in your perspective on all this, which seems to Germany like a historic watershed, but to many parts of the world naturally doesn’t.

Warm regards,

Georg

(In cooperation and with the generous support of Goethe Institute New Delhi / Max Mueller Bhavan)

Dear Georg,

I read your mail with great interest. The current situation across Europe is very intriguing, and I look forward to more details on how Germany is engaging with this sudden arrival of over a million people.

This morning I saw this arresting image (attached with this mail) of thousands of men, women and children walking in an orderly file through Slovenia en route to Germany. Clearly we are only just beginning to understand the origins and repercussions of this great migration.

I am also fascinated by the resurrection of old phrases and categories like “Abendland” or “the Occident”, and by this wonderful sentence where you say, “no sooner do I start than the entire vast history of the world washes over me.” It sent me down a digression that may be relevant in our thinking about the present moment in connection with the “new Völkerwanderung”.

You mention that many of the people moving through Europe come from Iraq, Syria, and the Turkish Syrian border, which correspond to the region once known as Mesopotamia – home to one of oldest recorded urban civilisations. The early Mesopotamian settlements traded extensively with the Harappan civilization, the ruins of which were found in present day Pakistan (another country you mention in your mail).

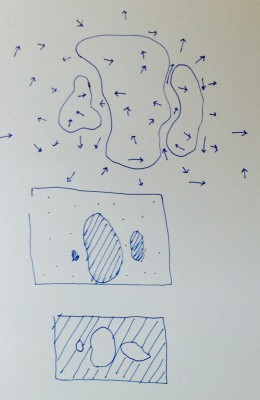

Recently a friend alerted me to historical research that contemplates the existence of a Harappan enclave – i.e. a colony of migrants from what is now called Pakistan – founded in in Lagash, a settlement in present day Iraq, in the second half of the third millennium B.C. It seems that the dawn of urban civilisation as we know it carries within it the seed of migration, and the history of the world is a chronology of struggle between the entropic, or disorderly, desires of people and the negentropic, or order-seeking, impulses of states.

Perhaps Europe’s current “crisis” signals a new moment in our shared histories? Perhaps this moment – when nation states in some of the oldest continually inhabited regions of the world (like Syria and Iraq) collapse – shall result in a re-fashioning of the critical categories of thought and language that we are accustomed to.

There are signs of this re-ordering already, with journalists, politicians and policy wonks wondering how to refer to this tide of humanity – are they migrants, or immigrants, or expatriates, or refugees, or asylum seekers?

Perhaps for the sake of this conversation we can refer to them as “Musafir” – an Urdu word common to Arabic, Persian and Turkish with slightly altered meanings in each language – A musafir is a traveller from a strange land, in some languages she is a pilgrim, a seeker of paths and truths, and in Turkish (I could be wrong here) I think, a musafir is a guest.

But why does this Musafir travel? Here we may consider a wonderful Persian phrase – of the concept of the ashina-zada, which refers to the feeling of tiring of all one’s acquaintances and desiring the company of strangers.

Perhaps this fluid category – of the Musafir, motivated by impulses that are not always obvious – is helpful in alluding to the long journeys taken by these people without diminishing the hardships they have suffered, or pre-judging the reception they will receive in Europe (as you mentioned, in some cases they have been met with violence, and in other cases with solidarity).

Your mail sent me down another line of inquiry, which is the narrative of the desperation of the Musafir – of course I have seen the pictures and read the harrowing accounts of boatloads of people drowning, of death by asphyxiation in abandoned freight trucks; the horror is real, visceral and immediate.

The amplification of this horror makes clear that the only politically feasible way Europe can engage with this situation is through the trope of humanitarianism. This narrative obscures the fact that in the years after World War One, it became a criminal offence to seek one’s fortune in a foreign land. While finance capital moves across the world with ever increasing velocity, we are fettered by our passports. There is, of course, a parallel imperial history of the passport – which we can consider another time: Who is to decide that I am Syrian, or German, and what does the act of name and fixing entail?

The current narrative of “rescuing the desperate” allows European nations and commentators to speak of humanitarian rescue and “European Values” without engaging with the strange, policed landscape that we live in, and accept the eternal policing of borders and residents as normal. What is the process by which it became normal and desirable for BMW to invest in a automobile factory in South Africa, but almost impossible for a young woman in a village somewhere in southern Africa to gather money from her network of friends and family, catch a flight to Germany, walk into a government office and register herself as someone seeking a job without constantly fearing imprisonment and deportation?

I think this “march of the musafir” offers us a moment to reflect on the long shadow of the twentieth century and the strange new categories it presented us with – borders, aliens, people smugglers, camps for those who cross a border without permission. It’s all a bit bizarre isn’t it?

Thank again for your thought-provoking email. I really look forward to this conversation and your descriptions of what’s happening on the ground in Germany. It is these details, after all, that shall help us think further and deeper.

Yours

Aman

Dear Aman,

Thank you for your mail, which sent me in two different directions. Way back to Mesopotamia, to where everything started. And to a future which is only just beginning to take shape. But that’s the way we live at the moment, time moves simultaneously backward and forward. This in turn – so goes the rapid script for our cascade conversation – reminded me of something that I read a couple of days ago, an article in the New York Times about the new findings of quantum mechanics. According to the report, physicists at the Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands conducted an experiment in which they proved that objects – in this case, the smallest of particles – affect each other even when far removed from each other.

Albert Einstein always rejected this theory, claiming it was as though God were playing dice. What bothered Einstein was the question of whether, in addition to the universe we know, there could be more – potentially infinite – universes. Whether, in addition to the reality we accept, there are other – potentially infinite – realities. Whether, in addition to the world we call our own, there are other – potentially infinite – worlds. Or as John Markoff describes it in the New York Times: ‘……the existence of an odd world formed by a fabric of subatomic particles, where matter does not take form until it is observed and time runs backward as well as forward.’

The wording is fascinating in many ways. Particles that take shape, in other words become reality and are therefore perceptible only when observed. Perception constitutes reality. And time that runs backward and forward. Here we have the question of whether time that runs backward processes all that went before. The modern in reverse – the results, forms and triumphs of the modern age change back into what was there before. However, what would this mean for democracy, human rights, individualism, secularism, nation and state? Is this what you mean when you speak of the crisis of the idea of the state, of a new way of thinking, other words, other philosophies and a freedom that does not come from the arbitrariness of a nation or from ‘German’ being randomly attributed to one who is born as a German and ‘Syrian’ to one born as a Syrian? That suffering, to some extent, must be accepted by birth and that freedom applies only to those who are free to claim it?

Yet atoms, particles that are separated, correspond, react to each other even when they are thousands of kilometres apart, as proved by the tests conducted by the physicists from Delft. Yet what does this mean for the way we think? What you said was right – money flows freely, people falter at borders. This is an untenable situation, a personal and moral insult representative of all of humanity. For a long, long time, columnists and other professional know- -alls have been saying that everything is linked to everything in a globalised world. But this reasoning was shaped purely by an economic perspective and it reduced everything to economics. It simply blanked out what it would mean if people were also to move as freely as capital. Money was released, and that had consequences. Now it is being followed by people. This has consequences too. In a certain way, both stand naked today, drastic in their existential rigour: the market and the human being.

For the people who are coming, are reduced. They are no more than what they are. They have nothing more than what they have and if even their dignity were to be taken from them, they would be left with nothing more than a plastic bag with which they have been on the move for months. They are naked existence, devoid of all civilisation. And civilisation responds by pretending they don’t exist. Some at least, and I fear there could be more. This is the daily shock of the images, the daily pain when looking at them. The people in long lines, wandering through no-man’s land, sometimes Slovenia, sometimes Croatia, sometimes Austria, the rain, the mud, the green of the landscape cruel, almost cynical, immobile, eternal, while the human being, the people, the families move on, vulnerable and in vain yet defiant, uncertain of what lies ahead, certain only of the fact that what they have left behind was what they found frightening, painful and threatening.

A trek of nomads in a world that left the nomadic way behind thousands of years ago. At least that is what is said. But perhaps it is different. And what you say is correct: the human being is old, something stirs in him, he sets forth, again and again, an old story currently being repeated. Time is there throughout, the entire history of mankind, in these pictures, breaking through the surface of the present that wanted to forget – and forgot – the multi-layered anthropology. Something is forcing its way through, and we are afraid. They walk and walk and walk, and it seems this is the way people originally were, walking, and yet to see it like this is surprisingly new and unexpected.

We must allow this shock to enter our language and thought. Only then can we perhaps understand what we are seeing, what is happening. Yet Europe is resisting the shock, in word and thought. We see destinies being transformed into policies, suffering into rules, need into measures. It is a sad, tragic spectacle, oppressive like Greek tragedy.

The six-year-old boy sleeping on the pavement, he is this boy and he is all boys, he has just arrived and he was always here. His mother, tired, his father, can he protect him? They are all parents, always have been, and are still pushing a rickety baby stroller through the dirt, right here, in the centre of Berlin, where we see scenes familiar only in Hollywood’s dark films, the end of civilisation as a fable, best enjoyed with plenty of popcorn.

Man is afraid of nothing as much as he is afraid of himself. Who is this musafir you talk about? A refugee, a wanderer, a traveller, a guest? Why is he travelling? What drives him? These are old, fascinating questions. The newspapers that write against the refugees no longer speak of ‘refugees’ but of ‘migrants’. This makes the masses controllable, bureaucratically manageable. They have started questioning basic human rights. They say this cannot continue, yet have no ready answer other than fences where people will die, and camps in which people will wait, wait, wait until they wait no more and run away.

I don’t know if this, what we are witnessing, is a ‘Völkerwanderung’ or rather a concrete reaction to concrete circumstances that have come about in the last 10 to 15 years, because of the war in Iraq and Afghanistan, of the failure of the West, of the iron hand of rulers in the Middle East, of poverty and injustice, of a war in Syria that was ignored, refugees who should stay where they are, that was the plan, the mistake, the moral betrayal. The countries there have already collapsed, the state here, in Germany, is also under threat, or so they say. I don’t believe it. It seems to be some sort of self-fulfilling prophecy, almost like conjuring up a state of emergency, that’s how extreme vocabulary is here now. They are talking yet again of Weimar, because here Weimar is the great shock of the past century. Those are the images they can recall. But the new events escape them. As does humanitarianism.

Yet there is so much that could be done now, that one could learn, there is so much that gives us courage. This is an old country in an old continent. It could open up, could re-invent itself. What does it mean for thought and thus also for politics if there is a shift in the world view? When things, people, separated by thousands of kilometres start to move? Does something like the discovery of a multiple truth, as shown by quantum mechanics, also have consequences for a different code of ethics? Many worlds exist only if observed by us. That is the shock that is starting to make itself felt, that is what explains the hatred and the aggression that are coming to the fore once again.

That’s the situation. And winter has yet to come.

All the best,

Georg

Dear Georg

Thank you for your thoughtful reply. These are all very important questions you raise; before I get to them let me share with you a story of musafir who travelled from Somaliland to Germany. It is a complicated story with many twists, but here I reproduce just a small section.

Let’s call him Abdul.

I met Abdul in 2012 at Berbera, a port along the Horn of Africa that also serves as Somaliland’s sole international airport. I was on assignment for my newspaper.

Abdul, who was working with a friend of mine in Hargeisa, picked me up at the airport. We got talking, and to my surprise, he spoke fluent Hindi.

Abdul also spoke fluent English, and German, and Arabic, and Telegu and Dutch and a smattering of Amharic. He had lived in Hargeisa, Mogadishu, Hyderabad, Mumbai, Addis Ababa, Tripoli, Basel and three different German towns.

He began wandering when he forged a Indian visa in the 1990s and made his way to the South Indian city of Hyderabad, where he worked as an enforcer in a local gang. After five years, he got bored of his life of crime and returned to Somaliland.

“But in a few months, I got bored of home and decided to go to Ethiopia,” he said, as we drove along the long straight highway that connects Berbera to Hargeisa.

He spent a few months in Ethiopia and then caught a bus from Bahir Dar to Khartoum, Sudan. From Sudan he made his way to Tripoli, and from Tripoli he crossed by boat into Italy where he said he was fleeing Somalia’s endless civil war and applied for refugee status.

His papers were processed and he was sent to Basel, Switzerland, where he was assigned refugee housing, given some financial assistance, but was not allowed to work.

“But what is the point of coming to Europe if you can’t work?” he said, “and so I started working illegally in an Indian restaurant. The owner really liked me because I could speak Hindi to all the Indian tourists who came to the restaurant, and of course because my salary was low.

“I would befriend the Indian tourists and offer to show them around the city. At the time many of the Indian tourists couldn’t speak good English – only Hindi – so they were very happy to find a Hindi speaking guide.”

Eventually the Swiss authorities found out that he had been working in violation of his refugee status and so Abdul decided to escape to Germany.

“Everyday I went to the Swiss-German border and I observed. The border police, they checked everyone and ask for papers – every car, every truck, every man, woman, child. They check everyone, except sportspeople.

“They don’t check the people who are on cycles, who wear cycling clothes, and a small bag on their back in which you can put maybe three pens. Every weekend, these people come cycling from Germany, they cycle all day in Switzerland and they go back in the evening.”

So Abdul buys a cycling costume in bright colors. He has no money to buy a bicycle so he buys a screwdriver. At night, he slips the shaft of the screwdriver through the shank of a bicycle-lock and steals the bike.

The next morning, he waits on the Swiss side of the border for the German cyclists and joins them soon after they cross the border.

Pedal, pedal, pedal pedal, along Basel’s picturesque streets; pedal, pedal, pedal, pedal, into the beautiful Swiss countryside. By afternoon, the cyclists loop back, the border looms, the policeman waves them through without checking for papers, and Abdul is in Germany.

In Germany he walks into restaurant, orders a beer and sips his beer till closing time when the owner asks him to leave.

“I tell the owner, I don’t know anyone here, I don’t have a place to stay. Will you help me? God will help you.”

Ok, says the German, you can stay here for just one night, and locks him into the restaurant.

“I don’t sleep. I clean everything: the windows, the floor. I cleaned all, I cleaned well, I wash, I dry. I clean the glasses, I clean everything.”

In the morning, the owner can’t believe his eyes.

“You are a worker,” the German says, “You stay with me from today and I will pay you money.”

Abdul stayed on in the restaurant, he married a German citizen, he had a son; he had marital problems, a divorce, and about five years after he left Tripoli, he came back to Somaliland.

“Why did you come back?” I asked

“It is a very complicated story, I had problems with everyone – my wife, Europe, the police, everything.”

A few months later, I was speaking with my friend from Hargeisa, Abdul’s boss, on the phone.

“How is Abdul?” I asked

“Who?”

“Abdul – the man who lived in India, and Germany and Sudan, and everywhere.”

“I don’t know. He is crazy. One day we had an argument and he left the job and vanished from Hargeisa. No one knows where he is.”

***

My reason for sharing this story is that I feel that the current writing about humanity’s march across Europe has produced the refugee as an abstract figure. In your email you write,

“The people who are coming, are reduced. They are no more than what they are. They have nothing more than what they have and if even their dignity were to be taken from them, they would be left with nothing more than a plastic bag with which they have been on the move for months. They are naked existence, devoid of all civilisation. And civilisation responds by pretending they don’t exist.”

How have you produced this figure of the refugee? What do you mean when you say they are “naked existence, devoid of civilisation”? Is civilisation a gift of the nation state, that you lose the moment you leave your home?

And who, or what, is this “civilisation” that “responds by pretending they [the refugees] don’t exist”?

Is Abdul – the musafir from Somalia – a naked existence devoid of civilisation?

No, he is an intelligent, ambitious, thinking agent of free will who sees an international border as a puzzle to be decoded.

European governments are eager to produce the figure of the helpless and desperate refugee because it suits them. If you are helpless, desperate and fleeing a civil war then you must be grateful for everything that Europe gives you – you must be grateful for a winter-proof tent in a large field with three meals a day.

This is the narrative produced by Power across the world; don’t fall for this trap.

In India, it is used by successive governments to justify the acquisition of community lands and the displacement of millions of people in the name of progress and development. It is a simple strategy in which a way of life is first stripped off all meaning, joy and value in public discourse. Then the intervention of the state is projected as an act of “humanitarian rescue”, a collective civic sacrifice at great cost to the taxpayer.

This “sacrifice” then justifies everything that follows. Luckily, very few people in India actually expect the state to rescue them from its own depredations.

At this point Europe’s governments are still pretending that they can actually control the march of the musafirs; that they can “solve” this “problem”. But there is no solution to the march of history – we can only live through it and hope to alter its course.

You ask: “Here we have the question of whether time that runs backward processes all that went before. The modern in reverse – the results, forms and triumphs of the modern age change back into what was there before. However, what would this mean for democracy, human rights, individualism, secularism, nation and state?”

I feel we need to stop thinking like the state – these are state-driven categories. They put the state at the centre of the conversation and we are reduced to making appeals to our local representatives.

America’s upcoming election is a fascinating example of how even the language used in electoral processes is completely exhausted and devoid of meaning.

If you haven’t watched the debates, I urge you to do so – these debates offer us a surreal and hopeful moment to think harder, think better, think sharper.

To conclude this email, let me leave you with another image: don’t think of the musafir as a naked existence plodding through a cynical landscape under police escort – this is a figure that doesn’t challenge your view of the world; this figure only produces pity and hopes for rescue.

Instead, imagine a young, muscular Somali man kitted out in sleek lycra and spandex, speeding across the Swiss German border on a stolen 7-speed bicycle.

He doesn’t need Chancellor Merkel to find a place for him in Germany – he has found it himself. Now how are we going to respond to, think through, and celebrate, his actions, choices, and life?

Yours

Aman.

Dear Aman,

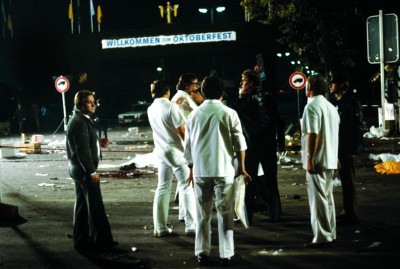

I visited Lageso again today. That’s what they call the official post in Berlin where refugees have to register. Landesamt für Gesundheit und Soziales [Office for Health and Social Affairs Berlin], abbreviated as Lageso.

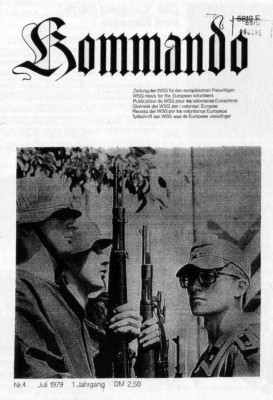

Like Pegida. Or Hogesa. It’s been an autumn of abbreviations with six letters. Patriotic Europeans Against the Islamisation of the Occident. That’s what one is called. And Hooligans Against Salafists.

These are the scary six-letter-groups that have changed Germany. Especially Pegida, who march through Dresden every Monday and are getting more and more radical. They carry signs that say “traitor” on them and have a gallows with them that they hold ready for Angela Merkel.

And yesterday I happened to read two columns that spoke of a “putsch” against Merkel. This is the mood in Germany at the moment. Just as The Economist is calling Merkel a model European, which isn’t true either, CDU politicians and political journalists in Berlin with bite reflexes are working to push Merkel out of office.

But what for? And why?

Back to Lageso. I was there for the first time in the end of summer. The people there were quiet, they were tired, they had made it. They were in Germany. There were about 400 people, I’d say, that were waiting to get a number, with which they’d continue to wait to get an appointment to make an application, which they then had to wait again to have processed.

That was strange to begin with. Even in Berlin, where a lot of stuff doesn’t work, an airport for instance, that’s supposed to cost 5.4 billion euros instead of 1.1 billion and may never be finished.

Is this Germany, some of them asked, the country where everything works and is on time according to cliché?

Is this Germany, many asked, when they saw the images of Lageso a few weeks after I was there, in late-September, early-October?

They were images of dismay, images of desperation, images of distress. “This is worse than in Turkey, worse than in Hungary,” said a Syrian refugee. “If I had the money, I’d go back.”

I was there one morning to behold the scene. Five thirty. Darkness. The shaded forms can be seen from a distance. They’re standing on the street, ten, 20, 200, more. Men on one side, women, children and families on the other.

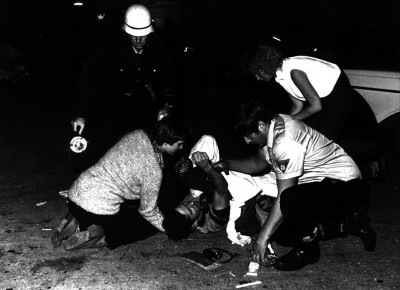

The door opens at six. The people make a dash for it to secure the best place, they want these numbers, they need these numbers, it’s all about numbers. As if in the 21st century they couldn’t regulate everything online that isn’t working here. Every morning the same scenes, ambulances driving off with the injured of the mad scramble.

Maybe it’s not supposed to work. There are stories of corruption in Lageso, there are stories of violence against refugees by security guards, there was a boy, Mohamed, who got lost in the chaos and was only found weeks later, abused and murdered.

“We will manage,” that’s what Angela Merkel said. The help and the openness of a large share of the population reflect this.

“We won’t manage,” that’s the mood that they spin, the media, the politicians. Images like the ones from Lageso are useful for demonstrating that it isn’t working.

The chaos is produced synthetically, so it often seems, so some say. The chaos shows we won’t manage.

And that was the point at which I had to cringe for a second when I read your mail. I thought, yes, you’re right, yes, that’s the view that I wanted to present, forms without dignity, without civilization. That’s the image that should be generated, because it can be manipulated to dehumanize the refugees, to reduce them, make them into an abstract quantity, into a number.

I wanted to present this mechanism to you. And I realized all of the sudden, that this sight, this point of view, this thinking has made a greater impression on me than I thought.

You talk about the state, the nation, the framework that the Europeans gave to politics – and you talk about it critically.

You say that it’s old thinking, that it’s dangerous thinking. And you’re right.

“What the Left has missed, is the utopia of internationalism,” my friend Nils recently said at lunch. If you believe in the nation as a solution for anything, then you’ve already lost.

But why did it sound for you like that’s what I wanted to suggest? Or did I even say it that clearly?

Alternatively: The state, the way it currently exists, may actually function better than the supranational constructions, the EU for instance, which degrades into egoisms.

Aman, how do you see an ideal order? What do you see for the future? What can Europe learn, from India, from other parts of the world?

What Europe is going through right now is a renationalization not only of thought, but also in politics. Egoism. Pop-psychological conjecture. Old role plays.

It is horrible. It’s as if you were to break through the base and realize that there’s no net, nothing to stop you and hold you up.

Is the continent breaking up again right now in front of our eyes? Sometimes it seems like it. The dramatic part of this is almost less, as you rightly say, that it’s breaking up, which is dramatic enough – the really dramatic part is that there’s a thought vacuum, a perplexity in policy, which you observed from a distance very well and precisely and better than I did.

In a certain sense you caught me. You noticed something in me that I don’t want to see. I consider myself to be outside of a world of thought that only talks about “self-defence” and “invasion” and “measures.” They just decided that Syrian refugees will only receive a provisional admittance and that there families in Syria won’t be able to join them here, where they would be protected.

They should remain amidst war, in distress and in misery. How can a country overcome this moral blemish? This kind of decision?

But am I myself so far removed from this policy? In your words a self-evident utopia appears, one that I’m missing. With the relentless news reports here it’s hardly possible, it seems sometimes, to lift your head up and regard the situation clearly and to see yourself in this scenario, one character among others.

You spoke of Abdul, who is a mentch, as my friend Igor would say, Yiddish for a person of integrity; he is a musafir, that’s what you call him, and it’s good that you told me about him, because of course there’s dignity in him, there is beauty and there is liberty in him.

But we want to see the people that are coming as weak. We want to see them as a mass. We also arguably want to see them as degraded, to whom we can give back some dignity out of our good graces.

We, we, we.

Who is this we?

It’s an awful train of thought you’re referring to. It’s an extremely Western, European, German view. It’s the egoism of colonists. It’s the white man’s burden, again and again.

Abdul, the mystery, the man that crossed the German-Swiss border in bright cycling gear, who was happy here and then again not, because happiness is an attribute not a condition. This Abdul that disappeared again, who knows where to – this Abdul is existence in the emphatic sense.

Not in this pitifully threatened, threatening tone, which is used when talking about the mass of refugees, as beings who remain in the minority in their passiveness.

A person is most dangerous, so it seems, and also most normal in what he or she does. Free and self-determined.

This person is the threat. For any order.

Thank you for showing me that again with Abdul’s story.

It was very quiet again today in Legaso by the way. I’m going to try and find out why it was like that today and what changed. And I’ll report back to you.

Sincerely yours, as always,

Georg

Dear Georg,

It seems Europe has changed since we last corresponded: Paris is stricken, Brussels is in lockdown and if early intelligence is to be believed, at least one of the attackers in the Paris attacks this November was traveling on a forged Syrian passport and breached Europe’s borders, to use a Maoist phrase, like a fish amidst a sea of migrants.

Islamic State’s use of a forged Syrian passport appears to be strategic – to make it easy for their agent to slip through borders, while simultaneously preying on European fears about Syrian immigrants. In sections of the public imagination, the figure of the migrant/musafir transforms once more: from one who flees terror into one who perpetrates terror. Some in Europe were waiting for this moment – Poland has already announced its intention to seal its borders.

France, the country that gave us the Déclaration des droits de l’homme et du citoyen, the rights of man and citizens (which didn’t apply in the colonies), is in a state of emergency where many of these rights stand suspended, and the question of citizenship is open to question. Earlier this year, French courts ruled it lawful to rescind the citizenship of dual-passport holders convicted of terrorism, effectively creating two classes of citizen. This interpretation of the French civil code was applied to man originally from Morocco, a former colony.

The journey of the musafir has suddenly become still harder. Does this mean, as some have suggested, that the terrorists are ‘winning’? I don’t think so, but let us set that imprecise question aside for the moment, and turn to your vivid account of your visit to the Landesamt für Gesundheit und Soziales, or Lageso – it offers us some ideas to think with.

It is fascinating that the Office for Health and Social Affairs is responsible for the registration of refugees.

It reminds me of Panopticism, the third chapter of Discipline and Punish, where Foucault describes how transformation of Power’s dreams can be read in the difference in its response to leprosy – which gave rise to rituals of exclusion – and the plague – which gave to disciplinary projects.

Those afflicted by leprosy are excluded from society; those with the plague are registered, numbered, quarantined to their quarters and continuously monitored by authority.

In this new form of power, which relentlessly partitions and subdivides itself down to the level of the individual, Focault writes, “The registration of the pathological must be constantly centralized.”

But what he writes next is even more insightful and beautiful, “Behind the disciplinary mechanisms can be read the haunting memory of ‘contagions’, of the plague, of rebellions, crimes, vagabondage, desertions, people who appear and disappear, live and die in disorder.”

So it is very important to document this process, as you have in your letter. The immigrant – a person who appears and disappears, lives and dies in disorder – is always a troublesome subject for a nation, because she destablisizes the category of the “citizen”.

Thank you for sharing this, and I look forward to more news and details of your visits to Legeso.

You ask, “Aman, how do you see an ideal order? What do you see for the future? What can Europe learn, from India, from other parts of the world?”

These are interesting and difficult questions.

Let’s start with the last one: what can Europe learn from India and the rest of the world?

I’m not sure if this particular email is the right place to delve into this in great detail, but in 1947 approximately 14 million people were displaced when the Indian sub-continent was divided into India and Pakistan.

There were riots, massacres, transit camps and incidents of compassion on both sides of the new border. My grandparents were part of this mass migration – they came from the Pakistan-Afghanistan border and settled in New Delhi. In time, in their new surroundings, the shock and horror of the partition lessened and presumably gave way to more banal and ordinary skirmishes, arguments and ultimately some sort of truce.

The memory of partition and the existence of Pakistan continue to inform a significant part of public discourse in India. Of late, supporters of our current government have taken to telling their critics to “go to Pakistan” if they express dissatisfaction with the policies and (in)actions of the ruling party.

This insult is often hurled by Hindus, who came from present day Pakistan, at Muslims who actually chose to remain in present day India. It is an interesting dynamic where those who chose to move challenge the patriotism of those who chose to stay: revealing the fragility of terms like “culture”, “migrant”, “original inhabitants” – terms that are used with great frequency, but with little sense of history, in current discourse.

My brief description of the Partition is a gross simplification of a long and messy process; but I think the broad lesson is that the current situation in Europe is far from insurmountable.

You ask – is the nation state breaking up? I don’t think the administrative frameworks of state-form are in too much danger, but I think the “nation-state” as a lens for understanding the world, movement of capital, interests of “people”, the deployment of labour, the assessment of fair wages etc, is becoming less and less useful.

Populations appear less interested in the nationality question, as is evident from the millions of people from the developing world trying their best to acquire a new passport. Rather than view the march of the musafir as the emigration of Syrians/ Iraqis/ Libyans/ Gambians/ Somalis to Germany/France/Austria/ Greece; let us view this as the march of labour to the citadel of capital in an effort to secure a new deal.

What if we consider this current process as a logical extension of the “Occupy” movements that we have witnessed across the world post “Occupy Wall Street”.

If the world is a single, increasingly integrated, economic unit (as we are often told it is), and every person is evaluated on her economic worth as a potential worker in this economy (as is usually the case) – then perhaps this summer was an instance of a global workers revolt, involving workers from Africa and the Middle East.

Adopting such a worldview may result in more useful solutions; particularly since the rest of the world is already viewing the migration along these terms.

Here’s an excerpt from a news report from the recently concluded emergency meeting on migration between the EU and African leaders at Malta.

“African leaders such as Niger President Mahamadou Issoufou say that $2 billion — which comes in addition to more than $20 billion that the EU and its members already contribute to Africa — is not enough. There should be less aid and more investment, they say, and multinationals should pay their taxes. The African Union estimates that the continent loses $50 billion annually through tax fraud and illicit practices by such companies.

“If we could combat tax evasion, that would stop us calling for aid,” Sall [Prime Minister of Senegal] said. “Terrorism is an issue, wherever war is waged people flee — where there’s less development people flee towards development.”

“We have to look at migration serenely, take the drama out of it,” he added.

Of course the pronouncement of African leaders reflect their own domestic compulsions – it is easier to explain out-migration from your country (say Senegal) if you can blame it elsewhere (say Europe) – but the suggestion to look at migration “serenely” suggests a realistic assessment of the limits of governance and coercion.

I’ll end here with some questions of my own. I am interested in knowing more about West Germany’s “guest worker programme” that saw millions of Turkish citizens come to work in German factories in the post-war boom. Looking back, how did this program play out, and is there any way in which the experiences of the 1960s may inform our thinking of the present?

As always, I look forward to your reply

yrs

Aman

Dear Aman,

I was in Paris for the second time. I was there after the attacks on the offices of Charlie Hebdo and saw people standing together, night after night at the Place de la République, because they were shocked, angry and sad – and thereby forgetting that they were only one portion of the city. The other portion of the city wasn’t at the Place de la République; they were outside, on the other side of the city walls, which have taken on the form of a highway today, but are similarly as insurmountable as they were in the Middle Ages. They were in the banlieues and they weren’t invited to the celebration of self-assurance. And some of them were openly celebrating the dead cartoonists and the dead Jews.

The mood was different ten months later. There were more deaths, but in a certain sense, it was the group of people who had lit candles at the statue of Marianne in January, who had become the target this time around. It was their friends or they themselves who sat in Petit Cambodge or in Belle Équipe, a few meters away from the Place de la République; it was their friends or they themselves who danced in the Bataclan. And, since it’s easier to mourn others than it is to mourn yourself, they were more quiet, more baffled, less angry and less solidary. They really were hurt, because they could feel in their gut where terror comes from: from their country, from their society, bypassing the war in Syria and fueled by the Islamists’ murderous mania. Nevertheless, they were kids that were born here.

I think it’s important to understand that. Because an attempt was immediately made of course to make that connection, between the terror and the refugees. That is cynical and wrong, and Mao has nothing to do with it. The people coming to Europe happen to be fleeing exactly the kind of people who killed in Paris. If there are a few terrorists among the hundreds of thousands of people coming, then that’s both statistically a strong probability and is absolutely a problem in terms of its implications for security; however, it’s not a problem that can be fixed by putting a fence up right in front of the refugees’ faces and thereby punishing the masses for something they’ve already been the victims of.

I think Slavoj Zizek said it quite clearly: “The greatest victims of the Paris terror attacks will be the refugees themselves, and the true winner, behind the platitudes in the style of je suis Paris, will be simply the partisans of total war on both sides. This is how we should really condemn the Paris killings: not just to engage in shows of anti-terrorist solidarity but to insist on the simple cui bono question.” He also wrote that the terrorists are “the Islamo-Fascist counterpart of the European immigration racists.”

And so both things actually do correlate – the terror and the refugees –, but not as plainly as a faked Syrian passport would suggest. Both fundamentalism and racism are extreme answers to a reality that is perceived to be increasingly complex. What gets lost here are the reasons for social tensions, economic inequality and tendencies towards societal breakup. I don’t mean that in a sweeping and overarching way. And a lot of the things that both fundamentalists and racists attack are things that I love and are important to me: freedom, individualism, hedonism. But there are also forces in the essence of capitalism that reveal themselves in this reciprocal violence. And Zizek also points this out: “We can’t address the EU refugee crisis without confronting global capitalism,” he writes.

What does this have to do with Lageso, with the Landesamt für Gesundheit und Soziales [Office of Health and Social Affairs Berlin]? You were right to point out the strange circumstance, in which a agency for public health is responsible for the question of refugees. And this is perhaps where the problem begins. Your association with Foucault was also very right. Because evidently what’s happening here, day for day in fact, is one thing: Discipline and Punishment. A veritable biopolitical regime reveals itself here; Giorgio Agamben would be appalled at how validated he has been now. The state manifests itself here in its contemporary biformity: as the administrator of conditions it created itself without laying blame – each individual is just an official in the machine; and as the dysfunctional extension of a system, which isn’t prepared for the almost metaphysical shift that awaits Europe.

Metaphysical? Maybe you’re right, I’m probably exaggerating. But that’s the mood at the moment – the insecurity, a bewilderment, that’s created with a specific goal in mind and is being exploited. The events aren’t metaphysical, they just appear to be so in the eyes of Europeans, which have adjusted to a few calm centuries. What’s happening right now between North Africa, the Middle East and Europe is rather routine in many parts of the world. And that’s exactly why what you can observe in Lageso, night after night, is so severe and alarming. The image of Europe is being deliberately destroyed here; the image, that Europe had of itself, as a continent of civilization or at least of civilizedness. Now you’ll say, Yes but at whose cost? Who were the victims of colonialism that were necessary for this civilizedness? Or you’ll say, There’s another whiny self-deprecating European, who enjoys nothing more than self-hatred.

I don’t know. All I know is that Lageso has made it into the New York Times by now, that there are online petitions and segments in the national news, that leading politicians are going there and writing open letters, that Berlin’s governing coalition could break up over it – and that none of that matters to me. Because it’s already taking too long. And because I’ve seen it for weeks and months, and couldn’t change anything. I wrote about it in my column and many people who agree with me read it. The others wrote vitriolic comments. I was there again after writing you; it was during the day and it seemed more calm and organized than it did during my first visits. But nothing had changed, as we now know. There was still the same chaos and the same arbitrariness. They were playing with people there.

And yes, it makes me angry. It may well be that Berlin’s government will fall in the end because of what it tolerated or created in Lageso, this intentional and inhumane mess in which children are lost and peoples’ hope, the most precious thing they still have, is destroyed. It’s the moment that will inform their image of Germany; and if they don’t arrive here, then they will withdraw back into themselves, and that in turn means that there will be parallel societies. But here it is the German state creating this situation of ostracization. Some lawyers in Berlin are filing charges against the senator of social affairs, and they are right in doing so. The pressure must grow. But it’s both sad and sobering that this situation had been tolerated for so long already.

The Front National just won in France’s regional elections. Donald Trump just uttered a few exceptionally dumb sentences: No Muslims should be allowed to enter the US. He’s a clown; but he’s a clown that wants to be president. And with each of his utterances of hogwash that get applauded, the measure of rationality slides a bit further to the right. And when somebody makes the suggestion of maybe only registering all Muslims, as Trump himself said a few days ago, then they even seem rational in comparison to the insanity of latter statements. It’s a sick cycle that can be observed here, a study of communicative dysfunctionality. Jürgen Habermas, the great theorist of communicative democracy, always started from the premise that participating parties are rational. But what happens when they simply denounce reason? How does legitimacy through communication work then?

These are the questions I’m concerned with right now. I’ll tell you about the history of gastarbeiter [guest laborers] in this country next time. With pleasure. And again about Lageso. Because everything is connected to everything else.

Sincerely yours, as always,

Georg

Dear Georg

Time has quickened its flow along the course of this conversation. The horror of the Paris attack is yet to recede, a fresh round of attacks is underway in Jakarta, and Ouagadougou in Burkina Faso. Earlier this week it was Istanbul.

I also read of the attacks on young women in Cologne over the New Year, the inevitable blowback, and Charlie Hebdo’s controversial illustration suggesting Aylan Kurdi, the Syrian boy who drowned en route to Europe, would have grown up to become a sexual molester.

The cartoon has drawn the usual reactions from the usual suspects, but it does signal a macabre closed loop of events that you refer to in your mail: the attacks on the offices of Charlie Hebdo, the refugee crisis, the Paris attacks, the violence in Cologne, and then a Charlie Hebdo cartoon to round things off. As you conclude in your mail – everything is connected to everything else.

Thank you for the reference to Zizek’s piece – I had missed in when it came out; and on reading it now – I was struck by an interesting passage towards the end:

“When I was recently answering questions from the readers of Süddeutsche Zeitung, Germany’s largest daily, about the refugee crisis, the question that attracted by far the most attention concerned precisely democracy, but with a rightist-populist twist: When Angela Merkel made her famous public appeal inviting hundreds of thousands into Germany, which was her democratic legitimization? What gave her the right to bring such a radical change to German life without democratic consultation? My point here, of course, is not to support anti-immigrant populists, but to clearly point out the limits of democratic legitimization. The same goes for those who advocate radical opening of the borders: Are they aware that, since our democracies are nation-state democracies, their demand equals suspension of—in effect imposing a gigantic change in a country’s status quo without democratic consultation of its population?”

Zizek responds, suggesting that Merkel was correct in not seeking popular consultation. He writes:

“Emancipatory politics should not be bound a priori by formal-democratic procedures of legitimization. No, people quite often do NOT know what they want, or do not want what they know, or they simply want the wrong thing. There is no simple shortcut here.”

I was interested in your perspective on this issue. What do you think about this limited section I have excerpted above?

I agree that popular consultation or a referendum would have made it politically impossible to accept refugees – but I instinctively disagree with his tired formulation that “the people” don’t know what they want, and so we need a principled vanguard to lead the way.

In many democracies, significant and irreversible decisions are occasionally solved by referendum; but it is interesting that nation states almost never call for a referendum before going to war – an epic and irreversible decision if there ever was one.

So I suppose the question is: Will the arrival of 4 million refugees to a continent of 750 million result in what you call a “metaphysical shift” in Europe – the sort of thing that should require politicians to go back to the people for their views?

Am I – by virtue of being far away – underestimating the long-term impact of Europe’s crisis ? As the optimistic resident of crowded chaotic city – 24 million and counting – I am inclined to think that we are simply in the initial “shock and awe” stage of this process, which will eventually culminate in some form of compact of coexistence between those already in Germany and the new arrivals.

I am in the midst of reading a fascinating new book – Poverty and the Quest for Life: Spiritual and Material Striving in Rural India – written by Bhrigupati Singh, an anthropologist at Brown University.

In his book, Bhrigu offers up the idea of “Agonistic Intimacy” – from the Greek “Agon” or “contest” – to try to understand how “potentially hostile neighbouring groups” might come together to forge a vibrant, yet contested peace by somehow including each other in their respective moral and spiritual worlds.

Living together in “agonistic intimacy” involves both conflict and co-habitation, and this subtle balance – Bhrigu reveals – has formed the basis of many human societies across time and space.

To extend this argument to the current predicament in Germany: it is possible that Syrian musafirs may not “integrate” immediately and seamlessly; but more likely the communities shall probably forge unexpected and possibly fragile bonds over a long period. Some bonds shall be largely symbolic, influential and fickle – one generation down the line, the child of a Syrian refugee might score a vital goal for the German national team or miss a vital penalty (I suppose here I am thinking of Mesut Ozil). Other bonds shall be less visible but enduring and intimate – like Syrian born workers in factories, Syrian-born nurses and doctors in hospitals. There will also be demagogues – of the likes of Trump, Marine Le Pen, and Nick Griffin, to contest and hinder this process at each step.

But is it impossible to believe that, given 20 years, these enduring bonds, prejudices, and encounters, shall converge into a mélange of myth, narrative, and ritual to consecrate the arrival of the musafir and the “recultivation” – to borrow another of Bhrigu’s phrases – of idea of the German identity and people?

The problem with Habermas’s “public sphere” – as you point out – is that he assumed that everyone will not just be rational, but will also publicly perform their rationality for all to see. This is demonstrably not the case.

A lot of politics, and most of life, is thankfully lived out of this public sphere. We are gradually realizing this in India where every week, a high-ranking government official or minister, says something implausible, violent or outright bigoted, with complete awareness that the national media shall amplify his (its usually always men) statements.

I agree that words have consequences, particularly when uttered by seemingly powerful people, but society has a fluid resilience – it coheres even as it transforms. It is this paradoxical resilience that keeps me hopeful.

Yours ever

Aman

Dear Aman,

This may sound a bit emotional, but I’m happy you exist. I am anyways, but especially am right now. When I write to you, it’s like I can beam myself out of all the insanity that I’m surrounded by on a daily basis. And I, like so many others, am suffering from it. People are talking about emigrating. For some people it’s just party talk. Others mean it seriously.

On the other hand, this letter beams me back into the middle of everything that’s happened in the weeks since I last wrote you. Is it still the same country? I don’t recognize the politics; I don’t recognize my colleagues. I can’t remember ignorance, meanness and resentment ever being bound together into such a hysteric, roaring bundle as quickly as they were after January 1st, 2016.

At the same time, I always have the feeling that I have to tell you something: Aman, be patient with me, I’m a European. We enslaved the world, but those were either my ancestors or, to a much larger extent, the British, the Spanish and the French. And we Europeans of today, we Easyjet-setters, are a strangely spoiled brood — we only know the stories of war and a life of affluence.

And a certain inexperience of the world is indeed actually one of the reasons for the excitement, for the political smear campaign, for the anti-constitutional suggestions, for the sheer opportunism that many are escaping into as if a new regime is already visible on the horizon and it’s about to be payday. Another reason may just be racism.

Refugees and “people with immigrant backgrounds” are no longer allowed to enter public swimming pools?! Refugees have to forfeit a significant portion of their money?! Mali is a safe third world country? Refugees have to wear a red armband, otherwise they won’t receive any money? The fact is, the people talking about the compulsion to integrate are the ones doing everything to make this integration difficult — mistrust, measures saying families cannot follow, and then lamenting that only “young men traveling alone” are coming to Germany.

It really is insane. 2015 was stressful. 2016 is insane. And the panic is growing, especially among the so-called people’s parties. The radical right-wing AfD (Alternative for Germany) party could supposedly receive 10 percent of the vote nationally. There are elections in March in some German states. And since one of the promises of salvation of the old Federal Republic of Germany was a stabil ‘party landscape,’ as the saying goes – Landschaft (landscape) is a very German word – that’s why this shift, which is a pretty unsettling shift among the old constellations, is almost a cultural breach for many.

They seem to really fear the pitchforks that an AfD spokeswoman wants to drive them out of office with. She recently said so at a demonstration. Political violence is suddenly on the table. On the other hand, there were 1,000 attacks on refugees or refugee shelters or generally-speaking anti-immigrant attacks last year. And this should be classified as terrorism, if you wouldn’t just rather – as many still would – talk about the “concerned citizens,” whose concerns need to be “taken seriously.”

This is the climate post-Cologne. Hardly anybody is talking anymore about the reasons people leave their homes and become refugees. The vast majority will only discuss the need to close borders, right now, unconditionally. They don’t talk about how to do that. They don’t talk about whether refugees, who still want to come, should be shot. They don’t talk about how Europe wouldn’t exist anymore, because Europe, this Europe, the one that wanted to put war in its past, is based on the free flow of people and dissolution of borders.

That seems to be all the same to you. You would rather talk about the return of the nation state, because you see what happened in Cologne as a failure of government. But a lot of people are quite gladly discussing the state now, which on the one hand is typical for this country, a country that has sought its fortune or better said misfortune in submission to authority; and on the other hand it’s cynical, because this call for the state, a strong state, often comes from those that wanted nothing, more each and every neoliberal day, than to get rid of the state wholesale.

But how does one come up with the idea of the nation state being a solution for an epochal phenomenon, like global migration? It’s obvious that they want to export weapons but that they don’t want to import the people that are fleeing the wars being wages with these weapons. But that won’t succeed. Because then they’d have to sacrifice everything that makes Europe what it is, at least constitutionally: freedom, equality, fraternity. And yes, you probably see things differently, they way my friend, Pankaj Mishra, does. In his book, From the Ruins of Empire, he analyses the West’s lies and crimes during the colonial period, drawing a connection between the democratic aspirations of countries like Iran, Turkey and China and interventions by the West. His conclusion is that Europe created an unjust world, which is now fleeing back to the origin of this evil by a devious refugee route.

So what, to put it differently, is a century? What is a century and a half? Circles eventually close but that’s not how people are thinking in these über-hectic times, and this is unique heckling. And the worst people are the ones that want nothing more than to drive Angela Merkel out, the crowds on the streets carrying gallows and signs that say “traitor” on them. But there are also the professors in the more reactionary sections of the daily papers, who say the same thing differently: Merkel betrayed “us” because her basic task is to prevent “harm to the German people.”

This is the sentiment behind what you quoted from the Zizek text. It’s one of the must unpleasant thought patterns, because it really is so reactionary, that’s currently making the rounds: Accordingly, egoism is the essential nationalistic kit, ethics are just for the good days, responsibility is for dreamers and humanitarianism is accordingly an episode in the European monotony. They’re riding with their backs to the sun. They’re reversing the course of history — this is their hope. However this plan won’t work, because in doing so, they’re taking away the breathing room. This is the danger. They detach Europe from the rest of the world. By trying to protect Europe with walls, with border fences, with boats in the Mediterranean and with arrangements with dictators like Recep Erdogan, they’re actually destroying it themselves.

Because the 21st century is the century of diversity. The culture warriors here don’t want to accept that. They rather spread the image of a murderous Islam, which automatically turns men into rapists. They rather fuel prejudice and hate, producing contempt for the democratic system. They’re acting like liberals, feminists and progressives, of all people, are to be blamed for what happened in Cologne. They’re truly ignorant. And sometimes I really can’t believe my eyes when I read some of the things they’re writing. And sometimes I have to question everything I thought about certain people.

Or about people in general. And this, to say something positive, has something thoroughly good to it. It’s a real reality check. And this is what you’re talking about. It’s what’s happening in the world. It’s the “agonistic intimacy,” which is what so many countries and cultures are made of. And yet, Europe has a strange phantasm, that of national homogeneity, something that’s hard to comprehend on a continent that’s been plowed through over and over by mass migrations. But maybe that’s exactly the fear that resurfaces in moments like these.

A historian just compared the current situation to the fall of Rome. Comparisons are dumb for the most part. This one was too. If the Romans had voted on it, would it have changed anything? If they had debated it? In the current situation, and this is what your question is getting at, it would certainly be difficult to hold a referendum for one thing. And I also don’t think that’s necessary. The essence of representative systems is what the people express by voting. I’m not an absolute advocate of this system. But it has its advantages. It currently guarantees a modicum of stability. Does Angela Merkel need to communicate differently, speak differently? Could she? Yes, with certainty. Parliament is the place for such a debate and it’s symptomatic and incorrect that this place is no longer being used.

The problem with the entire discussion is that it’s being held in such a defensive and fearful manner. But a few days ago, I saw how Justin Trudeau, the Canadian prime minister, casually and self-evidently explained why he took Syrian refugees into his country and why diversity is the future. And in Europe? There are politicians, from Poland in this case, that are seriously saying that vegetarians and bicyclists can not be allowed to be in power.

Aman, beam me up. Sometimes I really don’t know what I’ve lost on this continent.

All best,

Georg

Dear Georg,

apologies for this long absence from our conversation. (Also, Thank You! I too am glad of your presence and this conversation which gives us space and time to contemplate the relentless cycle of events.)

I would gladly beam you up, but alas I’m not sure where to bring you. No place seems to be free of nationalist hysteria coloured by a fear of imagined enemies.

The newspapers in India too seem to be from a different time: the president of the student union of Delhi’s Jawaharlal Nehru university has been arrested for “sedition” for chanting supposedly “anti-national slogans” at a university event. When he was produced in court, he was assaulted by flag-waving lawyers shouting “Long Live Mother India.” Journalists covering the event were beaten up as well.

There is a campaign to instill patriotic values in society; there is a proposal to install national flag, on 207 feet tall flag polces, on campuses to instill national pride amidst the student body.

In Hyderabad, a young man called Rohit Vemula from the historically-oppressed Dalit caste, hung himself from a ceiling fan in the student hostel – after he was hounded for “anti-national” activities.

He left behind an extraordinary note that offers fresh insights on each reading. I reproduce an excerpt below:

I loved Science, Stars, Nature, but then I loved people without knowing that people have long since divorced from nature. Our feelings are second handed. Our love is constructed. Our beliefs colored. Our originality valid through artificial art. It has become truly difficult to love without getting hurt.

The value of a man was reduced to his immediate identity and nearest possibility. To a vote. To a number. To a thing. Never was a man treated as a mind. As a glorious thing made up of star dust. In very field, in studies, in streets, in politics, and in dying and living.

Over the past two weeks I’ve witnessed extraordinary solidarity between students and teachers in JNU. Classes have stopped and teachers are giving public lectures that unpack and decode this strange thing called “nationalism”. Thus far, the student body has presented a united face to the government and police, despite deep political divisions between various political factions on campus.

In my interviews, I was struck by the diversity of the student base – many are the first members of their family to clear grade 10, let alone make it to university.

Prior to his arrest, Kanhaiya Kumar – the JNU student leader arrested for sedition – made a speech on campus where he laid out the contours of the ideological battle we are all living through:

What are universities for? Universities are there for critical analysis of the society’s collective conscience. Critical analysis should be promoted. If universities fail in their duty, there would be no nation. If people are not part of a nation, it will turn into a grazing ground for the rich, for exploitation and looting.

If we don’t assimilate people’s culture, beliefs and rights, a nation would not be formed….

I want to know what kind of nation worship they are talking about? If an owner doesn’t behave properly with his employees, if a farmer doesn’t do justice with his workers, if a highly paid CEO of a media house doesn’t behave properly with the meagrely paid reporters, then what is this nation worship?

So it is the worst of times, but also the best of times – in that a generation of students seem to be forging a politics of their own.

They aren’t cowed down by this assault on their universities, rather they seem to be growing in confidence each day; their utterances revealing a subversive humour and political sophistication that is completely lacking in the politicians entombed in parliament. It is all very fascinating to witness.

The news you convey from Europe certainly seems bleak; I just read the latest update that a group of Balkan countries have decided to come up with their own restrictions on migrants without waiting for the EU to come up with a plan. But maybe there are some silver linings to be sought?

On hearing about our correspondence, my aunt asked me when the world “refugee” first entered public usage.

It turns out that the word “refugee” was first used in the context of the flight of the Huguenots from France to England in the late 17th century after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685. So the first refugees – in the specific sense of the word – were Europeans fleeing religious repression in France. How can we interpret such coincidences or repetitions without being either cynical or facile?

Of late I have been reading a translation of medieval tales of fantasy, many of which are set in the bazaars of Damascus. Reading the rich descriptions of bazaars stocked with items most wonderous and magical, it seems impossible that such a world could end the way it has.

Perhaps the fate of the Hugenots, and Damascus, reminds us that it is a good idea to provide refuge to strangers as we never know when we might need the kindness of strangers ourselves.

Maybe that is the truly terrifying affect that the musafir or migrant produces: her or his appearance at the door is a gesture towards the ephemerality of our comfort. Could this ever be me? We think, before quickly suppressing the thought. I say this for all of us living in diverse and unequal societies – not just for Europe today.

It is not unlike George Orwell’s amazing insight in “Down and Out in Paris and London”, in the dialogue between Orwell and Boris, the Russian refugee who has taken it upon himself to show the young writer the ways of the street:

‘Do you think I look hungry, mon ami?’

‘You look pale.’

‘Curse it, what can one do on bread and potatoes? It is fatal to look hungry. It makes people want to kick you. Wait.’

He stopped at a jeweller’s window and smacked his cheeks sharply to bring the blood into them. Then, before the flush had faded, we hurried into the restaurant and introduced ourselves to the patron.

I’ve read Down and Out several times and always find this section the most powerful.

So I hear you Georg, but we beamed ourselves away, we’ll miss our chance to think through this unsettling time.

Look forward to hearing from you, as always, and apologies once more for the late reply.

Yrs

Aman

Dear Aman,

there were elections, state elections. The right-wing, radical party, AfD (Alternative für Deutschland), and their rejection of refugee policy achieved big successes. Some people are in shock, others are acting like nothing happened. I believe it’s a different country, that there’s been a rupture in time. And now the question of the before and the after comes back up. How can we recognize this rip in time, the one births misfortune, that leaks darkness? Isn’t there anything we could have done, have seen, have known?

But they’re everywhere, or am I fooling myself? The signs that we’re in a new era. And they resemble each other, they’re similar in many parts of the world. It’s an epochal break, and the contours of the new one, of the 21s century, are becoming more and more distinct. The values of the old word, the values that a large portion of humanity had settled on after so many wars and so much carnage, don’t seem to be so important anymore. They’re no longer attractive in a time when authoritarian politics are fueled by fear.

That’s what links Trump to Modi. That’s what I hear from you from what you recount in India; I hear it in the tragic, moving words of a man who killed himself because he was “against the nation.” It’s this foolish, deadly fiction, that’s primarily just a vessel of hate and violence and that gives people a sense of security; security that’s only achieved at the expense of other people’s insecurity. It’s prosperity that relies on injustice, peace that gives birth to war.

Europe is also transforming right now, and the refugees are just a trigger. It could have been anything. It was once the Jews. They could become the target of attacks again. But today it’s most notably the Muslims that have been pigeonholed as the bad guys, because they revere a vicious God – everyone knows this all of the sudden. Their God oppresses women and kills people. An Austrian politician just said in parliament, and wearing a red tie, that they’re the Neanderthals coming back, a species that was luckily eradicated in Europe a long time ago.

It almost makes me speechless. I wasn’t acquainted with this kind of language; at most, I’ve heard it in history books. I’m not religious, and I believe that all of the monotheistic religions have violent tendencies. Their logic alone tempts violence. But the aggression towards Muslims, and especially coming from educated people, surprises, shocks me. But what does that even mean – educated? People really like clinging to this catchword, which would suggest that you can describe where the evil is coming from – namely that there’s a different, dark cause, which is the opposite of an education, which is supposed to make sure that people know they’re not allowed to torture, that they have to stick together, that respect is the only path to peace. But is education a safeguard against stupidity?

Obviously not. A friend of mine is a musician. He calls me practically every day to complain about how racist the people in his milieu are when talking about refugees, how they generalize. They blame Angela Merkel for the migrant flows that have global causes; they obfuscate correlations that are so obviously clear and plain: Not only the wars and injustices that are causes of the refugees’ movements, but also internal injustices and conflicts caused by many years of wonky capitalism – capitalism that favored the rich above everyone else and gave many people the feeling that they’re no longer part of society, since promises of prosperity and advancement are hardly applicable anymore.

And if that’s the case? Then you can either get angry, which is one reaction – the authoritarian one. Or you think about how things could be different. That’s the other, constructive variant. I don’t say left or right, because these categories have lost their meaning in many respects. Authoritarian gist and fear are also inside people who would describe themselves as on the left. These categories have been offset – another part of the new world that we’re slipping into, without a plan, without certainties, fumbling, as we say here, for prospect, sometimes helplessly.

The thing people are afraid of is change. Hasn’t that always been the case? To me, being locked in an unchanging world is a dreadful idea. But the people who voted for AfD in three state elections en masse last weekend see things differently. Almost 25% in eastern Germany; 15% and 12.6% in the west. Concerned political commentators are now asking if they are all really right-wing radicals, as if there’s a litmus test for that.

I’ll tell you, I don’t care what people call them, whoever votes for a party that’s seriously discussing shooting refugees at the border, that’s spreading racist slogans and champions aggressive, egotistical nationalism, is so far away from what I consider democratically defensible, that one has to conclude that they want a different society. They don’t want a democracy. And so this election Sunday in March was really a break, and a cesura, for Germany, but also for Europe. It’s been hinted at already, this shift. It’s been proclaimed before. The pressure on Angela Merkel has been amplified by the media – her tone is a lot less humanistic recently than it was in summer and fall of last year. She increasingly seems to be returning to the old impulses of realpolitik. She does this even if many liberal or left-wing people see her as the only person to hope for, who they want to hope for, almost spitefully, since most of them didn’t used to have a friendly disposition towards this woman.