Every Tuesday afternoon at 3:30 I go to high school. The school is in Wedding, in a grand old pre-war building, with echoing halls, fluorescent overhead lights, and Koreans who can’t find their classrooms. I ignore their beseeching looks – I’m late to class myself – and take the stairs two at a time.

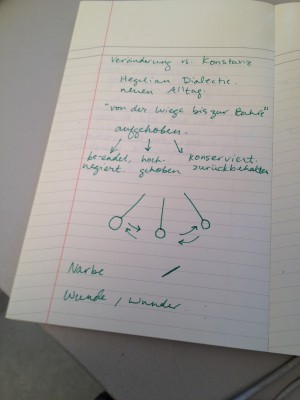

Inside Room 304, Reinhard, my philosophy teacher, is holding forth. I get out paper and pen and take furious notes:

Of course, I’m not really in high school. I’m just at the local Volkshochschule, an adult education center, which offers a philosophy class for non-native speakers. But everything about the setup screams being sixteen – sitting behind a desk; Reinhard’s easy charisma and wild gray hair, like the most popular high school teachers; the strong smell of floor wax; and my dorked-out joy, as I jot down the three different meanings of aufgehoben, and come up with a nifty pendulum illustration (which I’m pretty sure I also drew in 1998, when I was in high school in Singapore, learning about Hegel from my then-history teacher, Mr. Dodge). The fact that aufgehoben somehow simultaneously means nullified, lifted up, and held back makes more sense than anything has all week.

The Portuguese student raises his hand and volunteers a lengthy response to Hegel’s Dialectic, something involving Wunder that no one, not even Reinhard, understands. The Portuguese guy repeats it three times, to utterly blank looks, and then says forget it. This is a common occurrence. All of us can understand what Reinhard is saying, but we can’t understand each other, and find it hard to articulate, in German, what we think about being and nothingness.

Start over, Reinhard prompts the student. What does Hegel have to do with Wunder?

I think he’s talking about Wunde, nicht Wunder, says the other American woman in class.

Ja, the Portuguese guy says, relieved. Wunde, nicht Wunder. Wunde und Narben.

Wounds, not miracles. Wounds and Scars.

I jot this down, too. It seems like a crucial insight.

Later in the class, Reinhard hands out the poem “Stufen” by Hermann Hesse, and asks if we know the song “Turn, Turn, Turn” by Pete Seeger. There is a nervous silence, in which the American woman and I exchange looks, and somehow, I’m suddenly singing the song like I really mean it: “And a time to every purpose, under heaven.” I get a look from Reinhard like that’s enough before I hit the chorus, so I clear my throat and stop, disappointed that nobody claps.

That’s maybe the best thing about going to high school when you’re 32, you can sing a Byrds song without worrying if your bra strap is showing or if your shorts look weird or what the other kids think of the fact that you know the song by heart. And you can take notes that say “IMPERATIV! Stirb und Werde.” (Imperative! Die and Become.)