At the dawn of of rocketry, the work of the Berlin Verein für Raumschifffahrt (The Berlin Society for Space Travel) was particularly interesting. By the end of the 1920s, the Society’s launches at the ‘Raketenflugplatz Berlin’ (Spaceport Berlin) had garnered a fair amount of public the interest through newspaper articles and not least the fact that some of the rocket motors were loud enough to be heard from as far away as Potsdamer Platz. The German film industry had also taken note and at the time and director Fritz Lang was working on a big feature film for UfA titled Frau im Mond (Woman in the Moon), tangible proof for the great public interest in the subject at the time.

Lang decided to involve the Society to create a realistic depiction of space travel. Hermann Oberth, credited as a scientific consultant, and his colleagues helped design the fictional space ship called ‘Friede’ (Peace), largely based on Konstantin Tsiolkovsky’s sketches and to some extent on the Society’s own vehicles which at the time were still at the scale of today’s model rockets. In fact, at one point of the movie’s narrative, a model of the rocket Friede is scrutinized by experts before the actual voyage to the Moon, props of props.

The movie itself is remarkable in how much it anticipated images that were to be realized during the space race which was partly fought with cameras. (In ‘Fashioning Apollo’ Nicholas de Monchaux talks about how the American space program was largely to created for one photo – an American standing on the Moon).

Presumably because of the involvement of Oberth and his colleagues, Fritz Lang’s Frau im Mond pre-visualized with remarkable accuracy not only technological aspects things like rocket assembly facilities and launch pads such as the ones later erected at Cape Canaveral but also humans and liquids floating in weightlessness and even the famous earth-rise picture, taken on December 24, 1968 during Apollo VIII. Astronaut William Anders was so taken by surprise by this celestial photo-opportunity that it is safe to assume that he had not watched Woman in the Moon.

And there were yet more ways that UfA’s film project helped significantly advance early rocketry through a curious kind of fusing of the realities of fiction and engineering. Looking for a spectacle to promote and celebrate the first screening of Woman in the Moon at Berlin’s Kurfürstendamm in October 1929, UfA had intended to launch an actual rocket at the heart of Berlin and paid the Verein a significant amount of reichsmark towards design, construction, testing and launch. It would be been the first time for rocketry to cross the border from a functional model to an actual vehicle – funded by an industry which deals in fantasy.

The launch from Kudamm did not happen (luckily since according to Robert Nebel it might have resulted in a major disaster) and neither did an alternatively scheduled event to accompany the film’s premiere in the United States – the American release had overlapped with the emergence of ‘talkies’ and the interest in films such as Frau im Mond with all their over-acted jealousy and heroism immediately dwindled, turning it into the “last great silent film” – that never quite made it out of Europe. Its impact on space flight, however, was immense. The Society made rapid progress and was already making plans for the first manned vehicles when in 1933 the Nazis made it illegal for civilians to engage in rocketry. Tellingly, they also raided UfA’s production offices, seizing all props from the movie.

Meanwhile in the United States, Robert H. Goddard was launching rockets but nobody knew. Although he had published a range of scientific papers on the subject, his practical efforts at developing liquid-fueled rockets were unknown to Oberth and his Verein für Raumschifffahrt. They felt like true pioneers while in fact Goddard had made a first successful flight as early as 16 March 1926 in Auburn, Massachusetts. Unfortunately, there is only scarce evidence of the event, partially because the operator of the documenting movie camera had fled after apparently having been overcome by “fright” of the explosive device fuming in its metal launching frame. The rocket reportedly flew a short distance and then crashed into Goddard’s Aunt’s icy cabbage field. Years of experiments with ever larger vehicles followed until here as well the government realized the importance of the technology and stepped in.

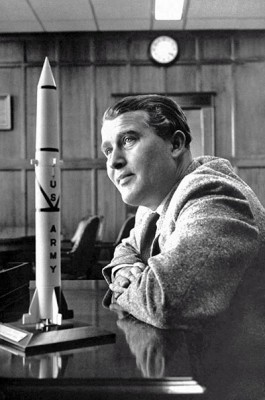

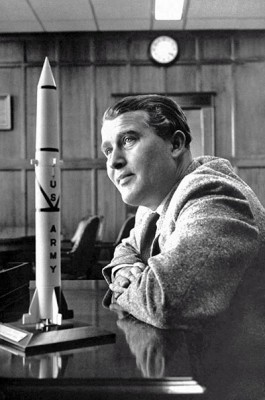

In Germany, the Nazis had devolved rockets back into formidable and terrifying missiles, in part because of their randomness owed to imprecision and malfunction, especially the V-2. It was created largely under the auspices of Wernher von Braun (second from the right in the photo above) and manufactured by an army of slave workers.

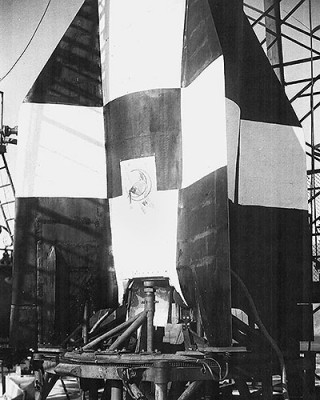

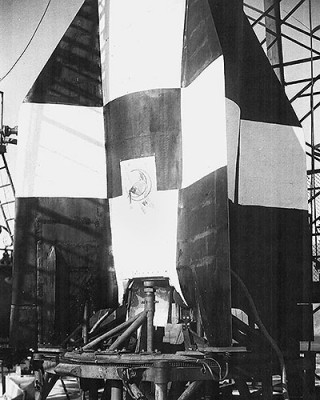

The launch operations at Peenemünde in northern Germany took further cues from Woman in the Moon, such as the countdown, the black-and-white markings of spacecraft, which were still found on ships like the Space Shuttle. Presumably to avoid more fright of camera operators von Braun’s engineers also gave CCTV to the world.

After the war, von Braun was whisked almost immediately to the United States as part of ‘Operation Paperclip’ and the American and German efforts at rocketry thus somewhat converged, leading to both the creation of intercontinental ballistic missiles and the Apollo program. Throughout his whole career at NASA he was mostly depicted with models of the creations of his agency – toys and trophies of an engineer.

In 1946, the first staged version of the V-2 called Bumper became the first human-made object to travel to space above the desert of New Mexico. Not only did this prove Konstantin Tsiolkovsky’s rocket equation right, it was also painted in the same black-and-white pattern of the rocket Friede and carried instead of a warhead a film camera, like in a scene of Woman in the Moon.