Sascha Pohflepp is an artist and writer based in Berlin and elsewhere. In his work and research he aims to probe the role of technology in our efforts to understand and influence our environment, extending across both historical aspects and visions of the future. His artistic practice more often than not involves collaboration with other artists and scientists. Sascha’s writing has appeared in magazines such as Under/Current and Volume and he is an editor with VVVNT. For the book Synthetic Aesthetics: Investigating Synthetic Biology’s Designs on Nature which is out now on MIT Press he has co-authored an essay on the notion of living machines.

Cans and Rockets, Part 4

In February 2014, Chris Woebken and I found ourselves on the way to M.I.T.’s Media Lab in Cambridge, Massachusetts, about an hour’s travel away from the town of Auburn where Robert H. Goddard had launched his first rocket in 1926.

On a whim, we stopped at a Toys-R-Us and bought a couple of Estes scale model rockets and motors with the intention of playfully re-enacting the launch. Upon arriving we found the historic site, now a golf course, completely covered in snow. We barely managed and were struck by how much it visually resembled the Moon.

One month after, we held the inaugural meeting of the Society for Speculative Rocketry – named in honor of the Berlin Society for Spaceflight – at Eyebeam Art & Technology Center in Chelsea, New York City. The aim of this ongoing artistic research project is to explore the practicalities of model rocketry in an artistic context, in part through building on the work of The Extrapolation Factory, a joint project by Chris Woebken and Elliott P. Montgomery, which provides a framework for speculative thinking.

Eyebeam’s main space was transformed into “the basement of a think-tank”, borrowing widely such as the windows of RAND Corporation, with a view on a virtual Santa Monica beach. Large tables were divided into sections such as ‘speculation’, ‘manufacturing’, ‘vehicle assembly’ and ‘vehicle display’.

After spending half of the day being taught how to build a functional model rocket by a volunteer from the Long Island chapter of the NAR, participants were provided with an array of inspirational material – historical photographs, Tsiolkovsky’s drawings, NASA’s visions of space colonies and more.

Those materials served as triggers for a guided speculation process in which the participants would build a symbolic ‘payload’, an object to go into the tip of the model rocket, a scale model, nested within another scale model.

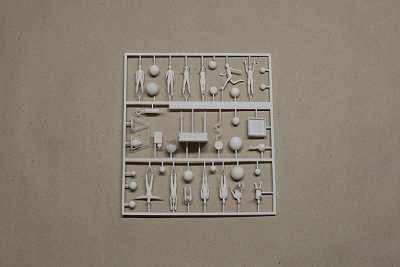

False memories, alternate presents, visions of the future or of the past. In addition to providing on-site 3D printing we also created a ‘Tsiolkovsky Kit’, a collection of items from the previously mentioned sketches, already in the shape of plastic models, thus short-cutting Tsiolkovsky’s visions and their later miniaturization as a scale model.

Day two, March 16 2014, saw a return to Auburn, MA in order to stage a performative re-enactment of Robert H. Goddard’s launch that had happened on the same day, 88 years ago.

One of the final models we launched was carrying a little camera. Although the camera was extremely light, it considerably altered the flight path of the rocket, making it ascend just a couple dozen feet before the motor burned out and the parachute deployed.

Upon viewing the video, a local expert in rocketry remarked that this flight must have almost perfectly traced Goddard’s first flight, producing the equivalent of a visual record for what wasn’t documented in 1926.

The Society for Speculative Rocketry is in a sense magical thinking through scale models. However, it is also an exploration of the dynamic flows between the wildly different ontologies that all happened within a single discipline of science and technology – roughly 150 years after Jules Verne had first published ‘De la Terre à la Lune’, a fiction which both Konstantin Tsiolkovsky and The Berlin Rocket Society cited as key inspiration.

Cans and Rockets, Part 3

At the dawn of of rocketry, the work of the Berlin Verein für Raumschifffahrt (The Berlin Society for Space Travel) was particularly interesting. By the end of the 1920s, the Society’s launches at the ‘Raketenflugplatz Berlin’ (Spaceport Berlin) had garnered a fair amount of public the interest through newspaper articles and not least the fact that some of the rocket motors were loud enough to be heard from as far away as Potsdamer Platz. The German film industry had also taken note and at the time and director Fritz Lang was working on a big feature film for UfA titled Frau im Mond (Woman in the Moon), tangible proof for the great public interest in the subject at the time.

Lang decided to involve the Society to create a realistic depiction of space travel. Hermann Oberth, credited as a scientific consultant, and his colleagues helped design the fictional space ship called ‘Friede’ (Peace), largely based on Konstantin Tsiolkovsky’s sketches and to some extent on the Society’s own vehicles which at the time were still at the scale of today’s model rockets. In fact, at one point of the movie’s narrative, a model of the rocket Friede is scrutinized by experts before the actual voyage to the Moon, props of props.

The movie itself is remarkable in how much it anticipated images that were to be realized during the space race which was partly fought with cameras. (In ‘Fashioning Apollo’ Nicholas de Monchaux talks about how the American space program was largely to created for one photo – an American standing on the Moon).

Presumably because of the involvement of Oberth and his colleagues, Fritz Lang’s Frau im Mond pre-visualized with remarkable accuracy not only technological aspects things like rocket assembly facilities and launch pads such as the ones later erected at Cape Canaveral but also humans and liquids floating in weightlessness and even the famous earth-rise picture, taken on December 24, 1968 during Apollo VIII. Astronaut William Anders was so taken by surprise by this celestial photo-opportunity that it is safe to assume that he had not watched Woman in the Moon.

And there were yet more ways that UfA’s film project helped significantly advance early rocketry through a curious kind of fusing of the realities of fiction and engineering. Looking for a spectacle to promote and celebrate the first screening of Woman in the Moon at Berlin’s Kurfürstendamm in October 1929, UfA had intended to launch an actual rocket at the heart of Berlin and paid the Verein a significant amount of reichsmark towards design, construction, testing and launch. It would be been the first time for rocketry to cross the border from a functional model to an actual vehicle – funded by an industry which deals in fantasy.

The launch from Kudamm did not happen (luckily since according to Robert Nebel it might have resulted in a major disaster) and neither did an alternatively scheduled event to accompany the film’s premiere in the United States – the American release had overlapped with the emergence of ‘talkies’ and the interest in films such as Frau im Mond with all their over-acted jealousy and heroism immediately dwindled, turning it into the “last great silent film” – that never quite made it out of Europe. Its impact on space flight, however, was immense. The Society made rapid progress and was already making plans for the first manned vehicles when in 1933 the Nazis made it illegal for civilians to engage in rocketry. Tellingly, they also raided UfA’s production offices, seizing all props from the movie.

Meanwhile in the United States, Robert H. Goddard was launching rockets but nobody knew. Although he had published a range of scientific papers on the subject, his practical efforts at developing liquid-fueled rockets were unknown to Oberth and his Verein für Raumschifffahrt. They felt like true pioneers while in fact Goddard had made a first successful flight as early as 16 March 1926 in Auburn, Massachusetts. Unfortunately, there is only scarce evidence of the event, partially because the operator of the documenting movie camera had fled after apparently having been overcome by “fright” of the explosive device fuming in its metal launching frame. The rocket reportedly flew a short distance and then crashed into Goddard’s Aunt’s icy cabbage field. Years of experiments with ever larger vehicles followed until here as well the government realized the importance of the technology and stepped in.

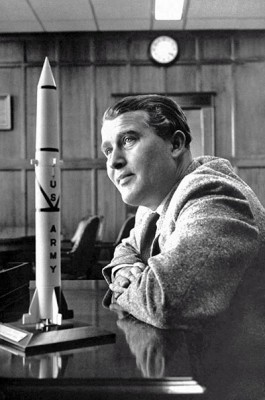

In Germany, the Nazis had devolved rockets back into formidable and terrifying missiles, in part because of their randomness owed to imprecision and malfunction, especially the V-2. It was created largely under the auspices of Wernher von Braun (second from the right in the photo above) and manufactured by an army of slave workers.

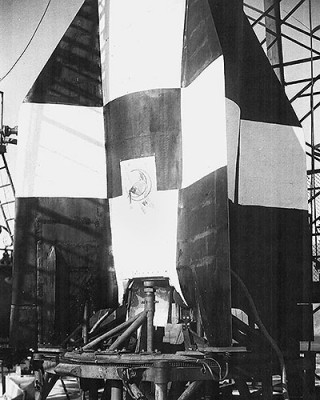

The launch operations at Peenemünde in northern Germany took further cues from Woman in the Moon, such as the countdown, the black-and-white markings of spacecraft, which were still found on ships like the Space Shuttle. Presumably to avoid more fright of camera operators von Braun’s engineers also gave CCTV to the world.

After the war, von Braun was whisked almost immediately to the United States as part of ‘Operation Paperclip’ and the American and German efforts at rocketry thus somewhat converged, leading to both the creation of intercontinental ballistic missiles and the Apollo program. Throughout his whole career at NASA he was mostly depicted with models of the creations of his agency – toys and trophies of an engineer.

In 1946, the first staged version of the V-2 called Bumper became the first human-made object to travel to space above the desert of New Mexico. Not only did this prove Konstantin Tsiolkovsky’s rocket equation right, it was also painted in the same black-and-white pattern of the rocket Friede and carried instead of a warhead a film camera, like in a scene of Woman in the Moon.

Cans and Rockets, Part 1

This series of posts, based on an artist talk delivered in April 2014 at LEAP Berlin, will focus on the role of scale models and simulation models, the former making something large or complex, past or not yet existing tangible, the latter constituting a computational abstraction which through its predictive qualities may end up having an influence on the world itself. Two projects will serve as examples, both collaborations with New York City-based Chris Woebken, created during a joint residency at Eyebeam Art & Technology Center: The Society for Speculative Rocketry and Elsewheres.

In its larger scope, the discussion also relates to another artistic research project, The Supertask, a collaboration with Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg initiated by the University of Southampton – an investigation into whether it would be possible to create a model of the whole world, or a world from models.

–

Scale models entered my world in 2009 when working on a piece titled The Golden Institute, a counterfactual history scenario set in the United States of a parallel universe. Here, Ronald Reagan has lost the presidential election of 1980 and Jimmy Carter remained in office. History tells us that Reagan swiftly abandoned Carter’s tender efforts at research and development of alternative sources of energy (perfectly embodied in the de-installation of a solar heating unit on the roof of the White House). In my narrative, Carter goes-all out on such technologies, turning the National Renewable Energy Laboratory in Golden, CO into The Golden Institute.

Carter, channeling his inner JFK, publicly states his ambition to make the United States independent from foreign oil before the end of the 1980s and endows the Institute with funds comparable to an Apollo-age NASA. Granted such powers, it pursues all kinds of projects, ranging from planetary scale weather-engineering in order to harness the power of thunderstorms in Nevada’s new ‘Weather Experimentation Zone’, all the way down to subsidizing individual Americans’ efforts to draw electricity from the artificial skies, an entrepreneurial vision of the mythical experiment that founding father Benjamin Franklin performed with his kite in 1752.

I chose to partially materialize parts of this narrative through objects for Douglas Arnd’s office, the fictional chief strategist, who is modeled after the likes of RAND Corporation’s notorious Herman Kahn. Scale models that are in fact trophies of the projects that make the Institute the most proud. One of them, a 1985 Chevrolet El Camino roughly at a scale of 1:20, is fitted with a huge lightning rod and towing a trailer full of supercapacitors to hold the electricity. It is everybody’s older cousin’s car, but modified to go lightning harvesting for profit, at approximately $400 per strike. The perfect demonstration of the way in which the Institute’s work has affected the lives of ordinary people.

Looking at the model’s 3D-printed parts, just moments before they were sent for chrome coating by the same London company that gilded C-3PO for Star Wars in 1977, I realized that I had created not a trophy but a toy – in fact one that very much resembles the ones I had been assembling as a child, mostly of American fighter planes.

Scale models do occupy a curious space between both past, present, future and in terms of our personal and collective imagination. My American fighter planes, often manufactured by Revell Plastics GmbH, a German subsidiary of a Californian company, are for instance in essence an iconic manifestation of real technologies. They were, gleefully appreciated, projecting American air power right into my kinderzimmer, billion-dollar projects distilled into a few grams of cast grey plastic. And, after successful assembly and decoration they may advance to being toys, elevated by imagination, and thus gain a performative function. But they rarely do fly.