Alexine loves patterns. She makes patterns that soften the world’s inherent hardness. It and she are a subtle solution to problems that you were only vaguely aware of only until it all becomes very clear. Her and the patterns are about joy in the end. You can sink in or bounce softly back on your feet as she does.

What Happened?

What Happened?

Scenario:

Malta. It’s 12:00, December 28 1977. Karen aged 15 and her little brother are home alone. A letter is delivered to their doorstep (we later find out he was a fingerless carpenter?). The small parcel was delivered whilst doctors in Malta were on strike (they had issues with the Labour Government at the time). The girl opens the parcel thinking it must be a Christmas gift. It works. The letter bomb explodes. She dies. At her funeral they say that this was “the first terrorist act in the country”.

Another letter bomb is delivered to Dr Chetcuti Caruana on the same day at the same time. He gets suspicious and asks his family to leave the house. He is right but the bomb is faulty. It doesn’t work. He lives. Later people blame him for Karen’s death.

Both bombs were semtex bombs that were activated as the lid is removed. Semtex is a plastic explosive, said to be used by IRA at the time.

The case remains unsolved. The suspects are a small number of Maltese doctors who reside in England and had close ties to the Nationalist party at the time and were closely connected to IRA who were mainly influenced by left-wing thinkers.

Some wonder if it is really sheer coincidence that this happened while the conservative Nationalist party where in opposition and stopped when they got into government in 1987 (some say they openly admired fascist Mussolini’s Italy pre and post WWII).

more…

In 1977, Chetcuti Caruana was a passionate spokesman in Malta Labour Party. He was then investigated in one of the most mysterious tragedies to have taken place in Malta – the killing of Karin Grech.

He was working at St Luke’s Hospital with Karin’s father Edwin Grech. Both were responsible for recruiting doctors during the doctors’ general strike. There were six doctors at the time. Karin’s father a gynecologist, had been working abroad but was asked to return to work in Malta. Dr Paul had close ties with Dom Mintoff (il-Perit, meaning the architect). He was the leader of the Labour Party at the time. Later Dr. Grech had been told not to return to Malta because they had no use for him here. Threats followed; don’t forget you have children.

11:45am December 28, 1977. It was a sunny day. The parcel had a palm print on it, the same palm print found on Karen Grech’s letter. Whoever was carrying it must have held on to it very tightly for fear the lid would come off. (Semtex bombs are commonly made to go off as soon as the lid is lifted.) Scotland Yard and the Italian Guardie came to investigate further. It turns out that the terminals were rusty preventing contact with the plastic and the bomb from setting off.

Dr Paul somehow realized it was a bomb. His family thought he was crazy, especially his father, who knew he had a fetish for secret service and military paraphernalia. He says he is not surprised for being one of the prime suspects. He was receiving anonymous phone calls just three days prior to the bombing attempt. Once, his wife answered one of these calls and heard requiem chants in the background. She pleaded her husband to quit Parliament.

During Karen’s funeral, the Archbishop broke into tears. This was the first terrorist act to have taken place in Malta. After Karin’s autopsy report, Pearl Grech (Karen’s mum) was visiting doctors’ wives, shaking the report in her hand, asking them if they had done this to her. Some said to ask ‘the mad man from Mosta Dr Cetchuti Caruana…..his bomb did not explode!’ Cetchuti Caruana was in deep distress. He cried. He was being questioned on how and were he sticks stamps to envelopes. It turns out that the address on Karen’s parcel was incorrect and the stamp was on the left hand side of the letter.

In 1991 he asked Nationalist Prime Minister if he had framed him back then. In 1995 Scotland Yard detectives said that this was clearly a political crime and those involved were leading politicians. He believes these bombs were a threat to Mintoff. His radical social reforms and his stand on Malta’s neutrality landed the government in hot waters at the time. Maltese doctors residing in London had close ties to IRA and were also suspected but never proven guilty. Forensic experts in 2011 revealed that after 34 years the investigators are still seeking fingerprints and other clues from 119 suspects. The plot is said to have hatched in the offices of the Medical Students Association where a telephone directory, envelopes and typewrites were all used there. A well known criminal with experience in explosives was commissioned to prepare these bombs, naturally at a price and perhaps blackmail as well. A very good carpenter – referred to in a Scotland Yard report, was engaged to prepare the small wooden container with two narrow compartments in it, which held the battery and explosive. The same person also used to allow the medical students and the other people to enter the legal office. Another person carried and posted the parcel bombs, one in Sliema and the other in Mosta. This person is likely to have been the same carpenter. He must have had several missing fingers, an occupational hazard commonly found amongst carpenters. It’s probably why palm prints where more evident then finger prints on the envelopes.

The case remains unsolved. The trauma remains.

What Happened?

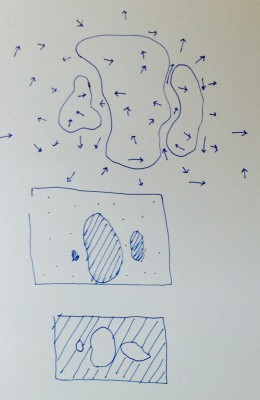

We spoke about walking around/inside the stories. We discussed presence and again scale. We agreed, size matters but is somehow relative. It depends on memory, on understanding, so also on language, politics and translation. So maybe size is personal and the stories’ presence should reflect that and possibly play with it too, mix things up. Logically 85 > 13 > 1 but maybe 1 > 85 < 13.

Phrases could (literally) outline each story, that would outline a memory hence an event. Our lines will be like traces(of each story) in memory, somewhat vague but still very present. We outline this void.

Almost similar to how a chalk outline (temporarily) marks evidence at a crime scene to preserve evidence. Surely ‘happier’ outlines exist. Like Keith Haring’s murals of technicolor, traces of forever dancing silhouettes.

tuttomondon; keith haring 1989 mural in Pisa

tuttomondon; keith haring 1989 mural in Pisa

We spoke about forgotten details, again the cigarettes, the fingers (or lack of), those triggers …surely there are more.

We could walk around/inside it. We could listen to the story in a language we might not comprehend but simultaneously read about it in BIG BOLD PRINT or in tiny tiny type somewhere else. We connect the shape with the sound and we mix things up but we remember. Also, what do we take away? What does this leave us with? Possibly new traces?

Still, what is the colour? What is outside? What draws the line? Is there a pattern?

This is how it could start. This is how it could be.

What Happened?

My first thoughts on bombs and bombers as ‘loners’ go straight to Karin Grech. She died when a letter was delivered by a fingerless carpenter to her doorstep some days after boxing day in ’77.

Why? I don’t know. How relevant this is to this conversation? I also don’t know. But it makes me question the relevence or contribution a reenactment of the oktoberfest attentat could have. I ask simply what? why? and how?

We start with a model of the situation. What is it made of? What does it say? Will the meaning change with scale? Generally speaking, it is easy to fetishize a situation when it is represented in a tiny scale, (think dolls houses and train sets?). It is also however, hard to fall in love with such a bloody event. What do we do with the 47 cigarettes? Do we shed light on other details linked to the scene but conveniently forgotten?

Working with models is usually simple and straightforward if you know your tools, your material, your glue. Here the game changes. The whole point should be the change. From the whole to the fragmented parts – parts which represent an exploded place/victims/story/past… What do we represent? How specific will it be? Maybe it is enough to start, explode, record and repeat. Maybe it’s good enough. For now…

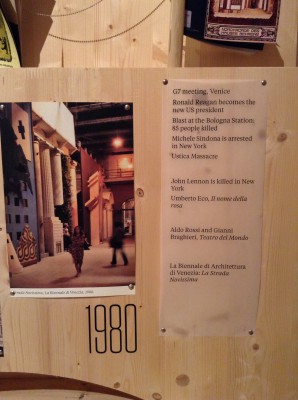

Here, in Venice there is no sign of the oktoberfest attentat in 1980 events that shaped architectural discourse. How strange. Maybe it was outnumbered by the Bologna blast. Maybe because simply 85 is bigger than 13. Maybe size does matter in the end.

radical pedagogies by beatriz colomina (venice biennale ’14)