I first met Emily in Beirut in 2006. We were invited to the Levant in the context of a rather badly organized art event curated by a player in the Beirut art market. My partner and I were underwhelmed but as soon as we were introduced to Emily who was working and living in Beirut we were compelled and surprised by her serious yet often humourous reading of the communal political hypocrisies at play within the confines of the various elites. It did make for intelligent fun. This was amplified by her invitation to the South of Lebanon for a little trip. It was a terrifying drive – she drove – and with it Emily narrated a brilliant, funny and precise reading of the various propaganda posters and flyers that lined the walls and the lamp posts as she speeded down the darkly lit highway. She seemed to have studied the local politics to such an extent that was unusual for someone of her age (she was 23) as was and is the timelessness of her humour. In general she makes one think better and harder and after many years having met her again and again in Berlin New York London we are certain that she is not of this earth.

The Refugees

It was the fall of the refugees, it was the fall that Germany changed back and forth and back and forth, unsure about itself, unsure about how to handle this challenge that some called a crisis. But really, a crisis for whom? There are people coming, desperate, dying, knocking at our door. Can you really deny them help? Can you really deny them the right to live as happy and pleasant as you? The answer of most people was: No, we have to help them. But this mood shifted. Emily Dische-Becker, a long-time human rights activist living in Beirut for years and now based in Berlin, has helped a band of Syrians to make their way to Germany. She accompanied them from Croatia to Berlin, she witnessed the difficulties of crossing the borders, she worked on a film which will be shown in 2016. She is an important voice in a time of free floating opinions and a public lost between hysteria and humanity.

Credit: Berliner Kurier.

A Nazi was hired as a lifeguard. You won't believe what happened next...

Two weeks ago, a 35-year old Cameroonian man named Anneck E. drowned at Berlin’s Plötzensee – across from the beach bathing club where lifeguard Mike Z. was on duty. According to numerous eyewitnesses cited in the media, Mike Z. simply ignored the man’s cries for help – as well as the cries of his family and people who were attempting to rescue him. “He just kept on opening his sunbrellas at a comfortable pace,” a man who tried in vain to rescue Anneck told the B.Z.

Mike Z. himself told the local daily:

“I did hear the bawling before. Then someone came and said there’s a guy drowning. But I can’t attend to that. I sometimes have up to 1,000 guests. How am I supposed to help when there’s someone drowning over there? Shortly after, someone came and said the guy was being reanimated.”

Curiously, the B.Z. makes no mention of Mike Z.’s recent past as an active member of the neo-Nazi scene. In fact I found only one news item about Annek E.’s death that references this – in a post on Berlin Online about a demonstration outside the beach club planned by an anti-fascist group.

Last summer, I had my first encounter with this “reformed” neo-Nazi.

In the past, I’ve found myself whispering “Nazi” under my breath during run-ins with run-of-the-mill German authority figures. Now that I was faced with the real deal, that seemed almost impetuous (reminding me of the many times I had mistaken a roll of thunder over Beirut for sonic boom from Israeli fighter jets. When it comes, sonic boom is unmistakable. So, too, was the Nazi.)

He approached our canopied booth at Plötzensee with a comedic woodenness and came to a stilted halt. Hands on his hips, he barked at us: “I wasn’t kidding ten minutes ago when I said you have to leave in ten minutes!” Except I hadn’t heard his original order. My lips instinctively began to form the word. I glared back and replied: “Well I didn’t hear you. Did I. (Nazi.)”

He was squat and blonde and sporting a short mohawk, and he continued to stare us down before making a sweeping gesture with his hand: “Well that doesn’t matter. You better be on your way. Now!”

My friend A. remained silent. The lifeguard’s eyes narrowed; he made a curt turn and goose-stepped theatrically across the sand. We begrudgingly collected our belongings and wandered across the sand toward the cafe on the opposite bank of the lake.

There, over beers, A. said that he had looked at the beach club’s Facebook page earlier to check the closing times. On the page, a discussion was raging over media reports that an ex-Nazi was employed at the club. Someone had posted a link to an article entitled, “Nazi supervisor at beach: Heil lifeguard!” which included photos of a certain Mike Z. seen at various neo-Nazi gatherings, and in one snapshot, striking the Hitler salute in the company of what the paper said were infamous neo-Nazis. The beach club management had recently published a statement defending its decision to employ Mr. Z, who had apparently left the neo-Nazi scene in 2010 and had been employed with the club since 2011:

“Mike declared his exit [from the neo-Nazi movement] to the intelligence services in 2010. The published photos are from before his avowed disengagement. The declaration he made to the service, as well as a further explanation given to us in which he—among other things—said that he had sworn off the mindset, had no form of contact (on or off the beach) to the right wing scene, and of course displays no right wing or racist behavior, were the basis and condition for his employment.

“On 15.04.2011, Mike was employed with us as part of a silent exit program. Since then he has performed outstanding work and never made a negative impression.

“Many of our employees have a migrant background and hail from the most diverse countries (from Cuba to various eastern European countries, to the US.) One of our patrons is a foreign Jew. Mike is fully integrated here, inconspicuous and popular. Many of our guests also hail from the most diverse countries and there have been no complaints over the past two years.”

In fact, a past news article in the Berliner Kurier had reported numerous previous complaints about racist incidents as well as attacks at the club (including a complaint filed in 2013 year with the police), emanating apparently from a wider contingent of Nazi-leaning employees.

Surely, people who have recently sworn off organized race-baiting need to find employment somewhere. Just not as arbiters of life and death.

Update: The Berlin police just released a statement saying that numerous criminal complaints have been filed claiming that the lifeguard didn’t rescue Anneck E., because of the former’s far-right views. “This suspicion has not been confirmed, according to the joint investigations by Berlin police and prosecutors. There is no evidence for the lifeguard’s culpable conduct.”

The statement also adds that maintaining the assertion that the lifeguard let Anneck E. drown could constitute a libel offense and result in a criminal complaint. I believe I have just laid out the facts here.

Jamal is from all over the place—Panama, Venezuela, Miami, South and East and West Lebanon. We met at a cafe in Beirut in March 2006. I had been reading—and was very amused by—his blog, which offered a satirical take on Lebanon’s sectarian political landscape, and pretended I wanted to interview him.

We soon began to collaborate producing radio features for a Pacifica affiliate in the US, and spent much of the 34-day war with Israel together (at a cafe in Hamra). I wouldn’t have survived that war without the Ghosn family’s generosity. Jamal risks getting bored without mischief, which is why he keeps me around. We have been running a nepotistic racket for the past eight years, and always find a way to get the other person a gig. Together we have passed through the halls and television studios of numerous media outlets. Jamal used to write the questions for the Arabic version of Jeopardy. He was managing editor for the English edition of the Beirut-based daily Al-Akhbar—a partner in the Wikileaks consortium. Recently, he left Beirut for Buenos Aires to dedicate himself fully to writing.

Jamal is a very astute political analyst and a bit of a math genius, but is decidedly shit at bets, which I—though far less knowledgeable—win every time. Over the years, he has paid for his folly in costly steak dinners, which is, I suspect, the real reason behind his move to Argentina. Here’s a new bet for you, Jamal: Given that Israel invades Lebanon during World Cup summers in which Germany failed to beat Italy (e.g. 1978, 1982, 2006), what will happen this year?

Teutonic order

Waiting feet

Among westerners in the global south, it is common to bemoan the locals’ lack of punctuality, akin to exchanging inane pleasantries about the consistently balmy weather. “Siesta time.” “Egyptian time.” The reverse stereotype – that of northern European punctuality – naturally exists, too, but is less pernicious a means of asserting difference. I once showed up a week late to renew my visa at Lebanon’s General Security. The official there fingered my passport and exclaimed: “But you are German! How can you be late?” When I explained that I had spent every day leading up to the visa’s expiration fretting about it, only to suddenly forget for an entire week, he commiserated and graciously let it slide. It was the summer of 2006 and we had established that we were both supporting Argentina in the World Cup. All was forgiven.

In Germany, where politicians and citizens are purportedly keen for foreigners to integrate into their value system, which naturally includes an appreciation for the sanctity of time, they greet the newly arrived with excruciating and arbitrary waiting periods. The expectation of rebuilding a new life, after a perilous voyage, is instead met with months if not years of dead time. If time is precious, then the first lesson you are taught upon arrival is that yours is less valuable than ours. “Making people wait… delaying without destroying hope is part of the domination,” Bourdieu writes.

The other day, we spent eight hours at the federal office for migration and refugee affairs (BAMF) in Spandau, five of them waiting in the hallway. Scheduled for eight, B.’s asylum hearing began just after noon. When we arrived, the waiting room was already packed, and so the best available position was to find a bit of wall space in the hallway to lean against. People stand, then crouch, then go outside and lose their wall space, then come back in. They shuffle, swing and tap their restless feet. video shortcode not working, usage:

[videoplayer url=… image=…]

Arab Spring hyperbole

(Or, how to commit Beamtenbeleidigung – insulting a civil servant – without paying a fine.)

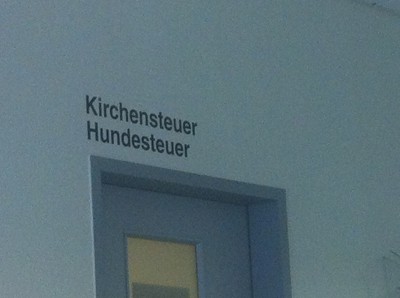

Yesterday, at the finance department in Berlin, I asked the official processing my tax forms if she knew why Mohammed Bouazizi, the Tunisian street vendor of self-immolation fame, had set himself on fire. “No,” she replied, her red pen scratching the boxes I’d failed to fill in on my application. She, like many state employees whose misfortune it is to interact with hapless citizens, didn’t display a particular fondness for questions; and I, I had already given in to bureaucratic fatalism and was planning my life on the run, as a low-income accidental tax evader. “Mohammed Bouazizi set himself on fire,” I said, “because of the infinite arbitrary cruelty of petty bureaucrats.”

She hadn’t yet heard that version of the “Arab Spring.”

Now she knows.

Every refugee knows

“When you are coming from a war zone, you can’t tolerate dead time. The most important thing is to start rebuilding something,” says Bashar Tamawi, a 33-year old urologist from Syria, who is currently holed up at an asylum center in Berlin-Gatow, pending his second court date. It took Tamawi three months to get to Berlin from Deir Ez-Zorr, where he performed over a thousand surgeries in a field hospital, only a stone’s throw away from the front line and often without electric power and sufficient medical supplies. The German authorities, some of whom may themselves in future require Tamawi’s services, e.g. for a prostate exam, should allow him to begin rebuilding a new life without further delay. And I should stop making references to prostate exams when talking to German asylum bureaucrats.

Tamawi’s asylum hearing is next week. The case worker who questioned Tamawi in Berlin promised him (and me) that it would not affect his asylum application if he detailed how he entered Germany. This is untrue. According to the Dublin convention, asylum seekers can be deported to their first point of entry in Europe.

Here is a wonderful profile of Tamawi from Wednesday’s Die Taz.

Hospitality wars

Syrian nuns apparently now rival Israeli soldiers as the most valuable hostages in the Middle East. Yesterday, in exchange for 13 nuns who had been kidnapped by a local Al-Qaeda franchise, the Syrian regime released 25 to 152 prisoners (according to state- and opposition sources, respectively).

Jabhat al Nusra reportedly treated the nuns really well during their three months of captivity, going so far as to describe them as “guests.” Upon their release, the nuns praised their captors as “sweet and kind” and insisted that “no one forced us to remove our crosses,” leading Syrian state TV to denounce the sisters as traitors and spies.

Jabhat al Nusra must have really pulled out all the stops for them: Lowering the treble and bass on the morning call to prayer. Christmas caroling (no stringed instruments.) Happy hour cocktails. Watching re-runs of Sister Act II.

The instrumentalization of minorities has reached new and obscene heights in Syria.

On that note, I overheard the following exchange between two young men at an airport bar yesterday: “Dude, who the fuck kidnaps a nun?” – “Dunno. Porn director, maybe?”

Assimilation

Bassem*, the youngest of six, has an older brother who has been living in Bavaria for some 30 years. He refers to him as “German Brother,” and while I’ve met this brother many times, I can never retain his real name. German Brother, like many Lebanese expatriates in France who voted overwhelmingly for Sarkozy, has developed strong opinions about the undesirability of immigrants. Especially Turks. When German Brother returned to Lebanon last summer, as he does every year, he regaled the neighbors with stories from Germany over coffee in the garden. “This Turkish delivery guy – what an idiot,” he said. “We live in building 22B. The dude couldn’t find it. He kept calling and calling me, stumbling around the premise. He didn’t know that building B is always in the back! Can you believe that?”

The story didn’t resonate, Bassem reported. In Lebanon, they make do without street names and house numbers.

Lebensraum

According to my mother, I had sworn off all forms of organized religion, and God’s very existence, by the age of four. Initially, the characteristic attributes of the Almighty were transferred to Mary Poppins, who I believed was all-knowing and vengeful. Our babysitter took advantage of this, sending us letters every day penned in the name of the indignant Disney nanny, detailing our misdeeds, compelling us to behave. Later, my fear of cosmic punishment grew amorphous, and so I tried to ward off misfortune by embracing standard commandments, such as Thou Shalt Be Generous Toward Strangers and Thou Shalt Not Be a Greedy Pig.

These, however, only apply on land. In the air, all social mores are naturally suspended; because flight is a matter of life or death. For this reason, and despite the extra legroom it affords, I always decline to sit in the emergency exit row on airplanes, where it is stipulated that one help others in case of accident. I have no intention of helping anyone get off a burning wreck before saving myself, but I’ve found that admitting this fact while the safety rites are being read will get you moved to an undesirable middle seat (my word processor tried to auto-correct this to undesirable Middle East).

On an airplane, I will shamelessly pursue any material gain to alleviate the discomfort of being sardined into a death trap with 230 wretched strangers. And there are others like me: frequent fliers without the class benefits. Those of our ilk lie in waiting until everyone is seated, and then find a better seat or row, and occupy it. We recognize eachother’s darting eyes scanning the aisles before the airplane doors close, and salute each other after a brazen takeover.

Then there are the others not adept enough at flying who are left sandwiched in next to their sweaty seat partners. They are often embittered and envious of our conquests.

And so it happened that one of these resentful passengers tried to intrude on the comfy lair I had arranged for myself on a recent flight from Berlin to Doha.

My original seat wasn’t all that bad – a two-seat row all to myself. But the adjacent center row boasted even better real estate: four empty seats. And so when the doors closed, I naturally moved there. An astute couple who had been seated behind me followed suit taking the row in back of mine. We bantered about our good fortune, and I soon got comfortable, stacking all the pillows on one side, wrapping myself in blankets galore, to try to sleep – and forget.

About 45 minutes into the six-hour flight, a young woman came and dropped her book down on the final seat in my row. Smack, it hit the upholstery. I raised my head and inquired as to what she was doing; she wanted to sit here (indicating with a sweeping gesture that she intended to seize the area that the bottom third of me was occupying) to “stretch her legs out a bit.” I suggested she instead take the two-seater that I had vacated, where she could have the same amount of space all to herself.

She glared at me and her eyes narrowed: But I want to sit here. – But it’s really the same thing if you sit over there, I countered. She issued a host of excuses about a special meal she’d ordered and about not wanting to move her suitcase, which I volunteered to move for her, until she finally announced to the whole cabin in a shrill voice: I think you are SELFISH.

Fine, I said. Are you trying to teach me a lesson, or do you actually want a more comfortable place to sit? (willst du mich erziehen?)

I want to sit here! she whinged. – Um, is this your first time on a plane? I feigned curiosity. This isn’t a social democracy, you know.

A silent staring match ensued, until she leaned forward and rang the bell to summon the stewardess, and proceeded to whisper in her ear in front of me. The stewardess looked puzzled, indicating that she couldn’t get involved in our dispute. And so, I laid my head back down and stretched out along the three seats; believing that I had deterred her, I fell asleep.

On planes, minor aggravations can quickly erupt into major confrontations. It’s like going home to stay with your parents for a spell, knowing in advance that you will helplessly regress, lose any sense of adult agency, and fall prey to ancient provocations. You can convince yourself you’re all grown up now and can defuse, rather than escalate, a silly argument over whose turn it is to unload the dishwasher (compared with the other incorrigibly truculent members of your family), only to toss all good intentions to the wind.

And so it was on the plane. I would stay and fight for my seat(s) until the bitter end.

I was awakened when the armrest between the two center seats I was occupying slammed down on my leg. I waited a second, then pushed it back up again. She slammed it down again. This time I kicked it up. I felt her feet sliding along the seats and digging into my shins. A kick. I kicked back, and raised my head: “Have you lost your mind?” I hissed. “Listen, you little snitch: Stop kicking me. I have to work tomorrow and need to sleep.” I considered lying about my profession. I am a pediatric orthopedic surgeon, you monster! Children in field hospitals will perish if I don’t rest. She was seething with contempt, but replied in a saccharin little girl’s voice: “But why are you so bothered by me? I don’t mind sharing the space with you.”

This prompted an Austrian man to get up and announce that he, too, thought I was selfish. He turned to the woman and declared, with a breathless appreciation for her commitment to the good fight: “In my opinion, you are right.” This alliance, at once new and time-tested, didn’t help my mood. “I don’t give a shit what you think,” I growled. “Mob moralists.”

I laid my head down again, but didn’t sleep a wink for the rest of the flight, expecting other passengers to enlist in their campaign against me. United by ancient contempt, my two enemies struck up a conversation that lasted until we landed. In the meantime, every time I dozed off, I was awakened by the seatbelt buckle clunking on my ankle, which I endured with a smile, or by the weight of a stack of books she’d arranged on top of my feet. Turning every once in a while, I’d toss the books off. She was not the type to be discouraged: lovingly, she re-arranged them, while chipperly conversing with her new Austrian friend. Neither of us slept.

When the lights went on and I sat up and returned to my original seat, the newly-found couple were planning a backpacking holiday together in Sri Lanka.